-

@ Pilgart Explores

2024-11-22 00:20:33

@ Pilgart Explores

2024-11-22 00:20:33What does a vegan diet have in common with London? They are both about as far removed from nature as possible. London is the world’s vegan capital, according to HappyCow’s Top 10 Vegan-Friendly Cities in 2024—like that’s a list you’d be proud to top… Just like London or any other global metropolitan megacity, veganism is built upon an industrial foundation. Veganism is functional, but it has no soul, no character, no unique traditions behind it. Allow me to explain.

Food is about more than nutrition

I’ve sat down to meals across the world, from the loud, bustling markets of an Andean town to a quaint French countryside brasserie. At first glance, these experiences may seem worlds apart. But dig deeper, and you’ll notice that both meals are simmering in a deep cultural broth, seasoned with passion and served with love for its tradition and roots.

To me, food paints a picture of the society in which it is made. When I’m eating a dish, the food tells a story about the people who created it. It provides answers to questions like no person ever could.

When I sit down to order from a menu offering stews brimming with freshly picked herbs and vegetables, roasted meats from animals raised nearby, and fruits plucked directly from trees, I am filled with excitement. It is hard to decide what to order, as the smell from the kitchen glides by, I can’t wait for the first bite.

Mercado Vega in Santiago de Chile

Mercado Vega in Santiago de ChileVeganism: A Diet Born of Industrial Convenience

The further away I travel from global metropolitan megacities, the clearer it becomes: veganism is a diet born not of nature but of industrial convenience. It’s not a lifestyle that embraces the flourishing of the planet or humanity. Instead, it relies on factories to transform soybeans and chickpeas into something they were never meant to be—human food.

The more I explore the world, the more I realise veganism isn’t about connecting with nature; it’s about reshaping nature to fit a modern utopian fantasy. A fantasy created in a global metropolitan life, where everything looks, feels, and tastes the same—whether I’m in London, New York City, or Kuala Lumpur.

Try crossing the Namib desert on a vegan diet. You’ll turn back before the first day has gone, desperately hungry and searching for the nearest vegan restaurant—nowhere to be found. You’ll face a choice: Do I want to cling on to this utopian fantasy of what’s "natural," or do I eat the delicious food nature has already provided in abundance?

Game meat is plentiful in this serene, natural environment, as are fruits like melons, dates, and oranges. If you’re lucky enough to meet one of the nomadic Himba tribes who roam this vast desert, you might even be able to trade your way to goat. Out here, in the real world, nature won’t present you with a tofu tree or soybean plant.

It’s almost as if Planet Earth is sending us a message: eat what’s readily available, what doesn’t need heavy processing to become food.

A traditional Himba lady, Namibia

A traditional Himba lady, NamibiaThe Soybean Assembly Line

The irony of veganism lies in its branding—as a natural, healthy, and environmentally friendly choice. Clever marketing, but utter nonsense.

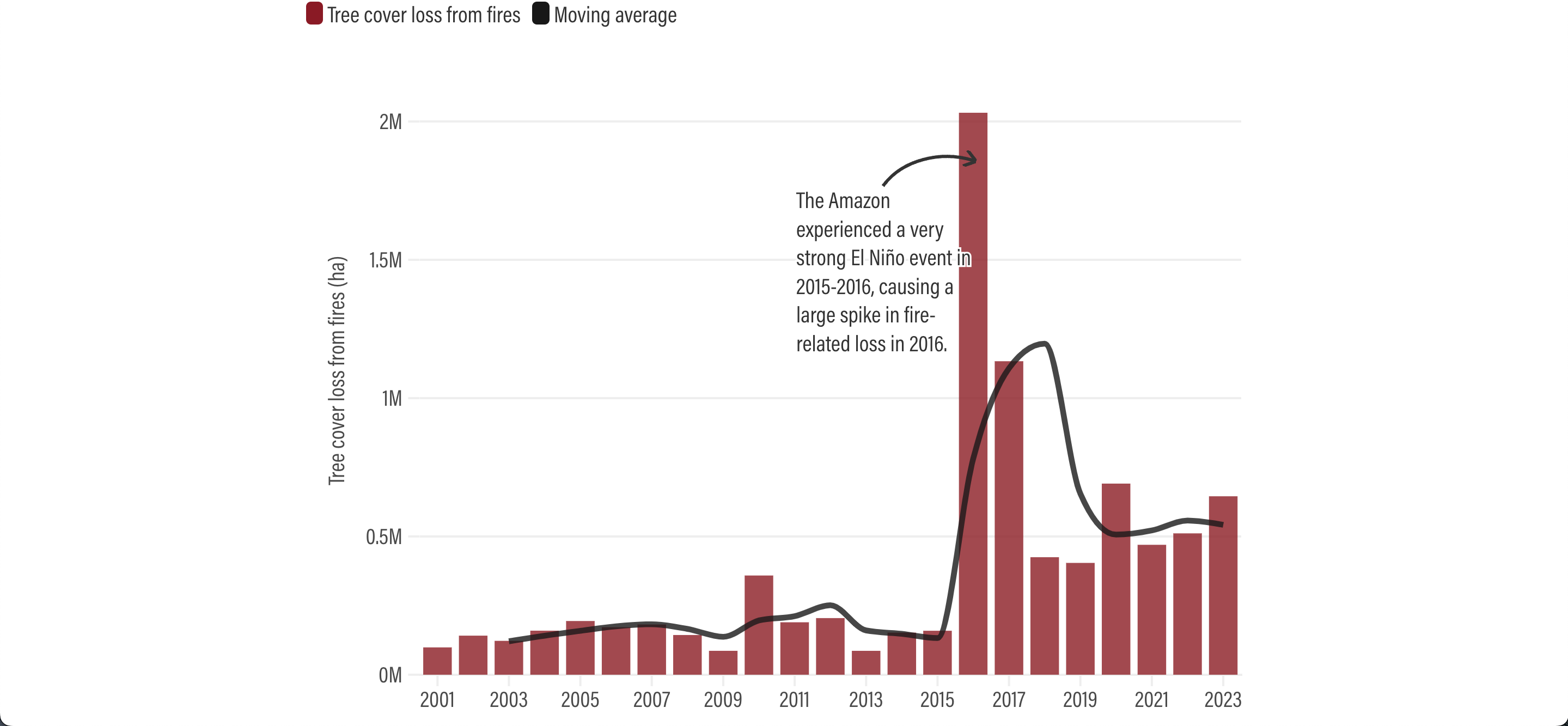

Soybean farming, a stable of vegan food, is one of the leading contributors to deforestation in the Amazon, alongside gold mining. Vegan advocates might argue that most soybeans are used for industry and animal feed, but they conveniently overlook the inherently unnatural nature of soybeans as human nutrition.

For instance, producing one litre of soy milk requires 300 litres of water. Add to that the seed oils, artificial colorants, flavors, textures, and E-marked chemicals listed on vegan meat and cheese ingredient labels. Barely anything about vegan meat or cheese is natural. It’s a synthetic symphony—carefully assembled in factories, stripped of the raw nutrients found in real, whole foods.

The hypocrisy is striking. The vegan industry presents itself as the solution to climate change, yet its reliance on resource-heavy, industrial processes undermines that very claim.

The three-year moving average may represent a more accurate picture of the data trends due to uncertainty in year-to-year comparisons. All figures calculated with a 30 percent minimum tree cover canopy density. Source: UMD GLAD Lab.

The three-year moving average may represent a more accurate picture of the data trends due to uncertainty in year-to-year comparisons. All figures calculated with a 30 percent minimum tree cover canopy density. Source: UMD GLAD Lab.Why Do They Want You to Eat Vegan?

So, who’s behind this "veganism good, real meat bad" narrative? Look no further than the architects of the climate change agenda—organisations like the World Bank, the IMF, the World Economic Forum, and companies like Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods. Investors like Bill Gates, through initiatives like Breakthrough Energy Ventures, also play a significant role.

These are organisations and individuals who operate without principles like open debate in search of truth, instead they don’t like to be challenged on their believes, they are afraid to engage in public discourse, like podcasts and freedom of speech based platforms like Substack. These organisations expect you to buy into their message, fall in line and don’t ask questions - The most outrageous examples are ESG policies and carbon credits - a giant coercion machine designed for those in the know to profit off of the actions they coerce individuals and businesses to perform. Do take that as investment advice if want…

As I see it, the most horrifying example of what the ambitions behind, vegan lab food and the climate change agenda is. Is the article published by the World Economic Forum titled “Welcome to 2030. I own nothing, have no privacy, and life has never been better”. I can’t help but wonder if in 2030 we will all be eating vegan lab food, driving electric cars and living in urban areas, whilst being completely dependent on an internet without any privacy. In this dystopian future, it will be possible to turn any disobedient citizen off with the click of a button. Governments will have complete control of all lives, like an all seeing super God. They will control what you eat and at the click of a button, suddenly your computer won’t work, your money won’t transact and your car won’t drive. Just because you had a differing opinion.

The luxuries of the real world, being in touch with nature, experiencing nature in its beauty and magnificence will be for the few. The luxury of travel or living a self sufficient life, will be for the ultra few - The few that told you to eat vegan, move to the city and never step foot on an airplane, because an airplane destroys the planet.

Remember if your opinion is based on the annihilation of other opinions you don’t agree with - then you have no opinion at all.

The article was originally posted to Forbes.com but seems to have been taken down from most places online. I was only able to find the article in Medium

The article was originally posted to Forbes.com but seems to have been taken down from most places online. I was only able to find the article in MediumCultural Disconnect: Food and Identity

I travel to experience different cultures, to better understand cultures, that are different from here I grew up. I travel to broaden my perspective on the world and the people that make up this wonderfully crazy planet, that we all call home. I also travel to enrich my taste-pallet. I love food. Food is a window into a society’s traditions, history, and identity. When I sit down for a flavourful Paella at restaurant in Valencian side street, I am eating a dish that tells me about Spanish history. The aromatic sweet saffron known as red gold, that gives the paella its distinct taste, came to Spain with Arabic tradesmen that conquered large parts of the Iberian peninsula. The tomatoes arrived on my plate from the Andean mountains in South America, brought back to Spain by the conquistadors of the Spanish empire.

The paella is history lesson in itself. The Paella tells the story about the territory that we know as modern Spain. The Paella tells me, that Spain was once dominated by islam. Which hints at why the famous Spanish Flamenco music, has so many sounds, that sound oddly familiar to the music of the Arab world, I heard when I was travelling around Turkey. The Paella also tells me about Spain’s history as a global empire reaching far beyond the shores modern day Spain. Food is about a connection to culture and history. Food is able to build connections between different cultures.

Food Connects Cultures

It was a hot autumn afternoon, I was walking around Diyarbakir, the capital of Turkish Kurdistan. In the background the local mosques were calling for prayer, but I wasn’t heading for the mosque to ask for forgiveness for my sins, I was on the hunt for some food, some local food. I thought to myself “hopefully I can meet a local and establish a connection”. It was my second day in Diyarbakir, so far I had mostly communicated with the locals via hand signs, google translate and the sort broken English of a five year old, I find myself opting for, when ever I speak to someone who barely knows how to say “how are you?”.

My eyes caught two young men in the midst of installing a projector in the covered terrace area of one of the local restaurants. Inside there was a handful of tables with men drinking Turkish çay tea and smoking shisha pipes. They all looked at me with a welcoming smile and a facial expression of general puzzlement of my presence. Not many European foreigner venture to the southern parts of Turkey, where the Kurdish people live. The area is near the Syrian border and Kurdistan has long been painted as terrorist area.

As I approached the restaurant the waiter pointed me to a table, handed me the menu then with broken English and few hand gestures, he signalled for me to wait. I proceeded to investigate the menu, of course all in Turkish, I had managed to pick up some the basic words necessary for ordering food during my travels. I wasn’t completely lost in translation. The waiter came back with another young man, my age, Bawer. Bawer sat down in front of me with his cigarette in one mouth and his ashtray in the other. He offered me a cigarette, I politely accepted, then he said “How are you?” “Do you need any help?” His eyes lit up when I said I had my eyes on the Saç Tava, a Turkish stew with tomatoes, vegetables, chilies and mouthwatering tender lamb, and asked if he could recommend that? Bawer said “It’s my favourite dish but be careful it’s spicy”. I offered to order for him as well but he said no thanks. I ordered food for me and pot of tea for us to share.

Bawer and his friends

Bawer and his friendsThis was how I met Bawer, Bawer spoke great English and was able to answer all my questions about Kurds and Kurdish identity, the historic fights between Kurds and the Turkish government. The next day I met back up with Bawer and two of his friends, they gave me a tour of the city, told me all about life as a Kurd in Turkey. In the evening they even invited me to a Kurdish wedding from one of their friends, but these are stories for another day.

Conclusion

My point is: In this utopian fantasy world of the future, where we are all vegans. All food will be produced in labs and factories. All food will taste the same, no matter where you go in the world. If that becomes the reality, then this experience and countless others just like it, would never happen. Local culture would slowly die, so would beautiful spontaneous meetings, with strangers over food in some foreign, far away place.

If that is where the world of tomorrow is going, then I’m glad I got to see it beforehand.