-

@ 35f3a26c:92ddf231

2025-01-22 20:48:34

### Background

Most people non familiar with Bitcoin thinks that there its has not smart contracts capabilities, and that is incorrect, there are smart contract capabilities, and despite limited in comparison with other blockchain networks, those capabilities are evolving slowly but surely.

The support for smart contracts is done through its scripting language, Script, which allows developers to create complex conditions for transactions.

**What can you do with Script?**

1. time locks

2. multi-signature requirements

3. other custom logic

opcodes like OP_CHECKLOCKTIMEVERIFY (CLTV) and OP_CHECKSEQUENCEVERIFY (CSV) are used to build more sophisticated smart contracts, these opcodes enable features such as the Lightning Network, a key scaling solution for Bitcoin

back in 2021, the ***Taproot ***upgrade introduced Pay-to-Taproot (P2TR), in summary allows for more private and efficient smart contracts, in that soft fork more was added, in addition to Taproot, we got as well ***Schnorr signatures***, which enables multiple signatures to be aggregated into a single signature, improving scalability and privacy and ***MAST (Merklized Abstract Syntax Trees)*** which reduces the size of complex smart contracts, making them more efficient, as an added value, this efficiency reduces the cost of transactions.

The ***Taproot ***upgrade has laid the foundation for the development of more sophisticated smart contracts on the Bitcoin network, and the use of covenants is an important part of this development.

### What is Bitcoin Covenants?

It is a **BIP** (Bitcoin Improvement Proposal), **BIP-347**, assigned on April 24, 2024, which marks the first step towards reintroducing functionality removed from Bitcoin by its creator Satoshi Nakamoto in 2010. This proposal aims to bring smart contract functionality to Bitcoin as we see in other EVM networks.

The proposal’s developers authors names are **Ethan Heilman** and **Armin Sabouri**, now the community will debate its merits.

Here the link, in case you are curious:

***[https://github.com/bitcoin/bips/blob/master/bip-0347.mediawiki](https://github.com/bitcoin/bips/blob/master/bip-0347.mediawiki)***

It is worth to read the motivation section of the BIP, which reads:

“Bitcoin Tapscript lacks a general purpose way of combining objects on the stack, restricting the expressiveness and power of Tapscript. This prevents, among many other things, the ability to construct and evaluate merkle trees and other hashed data structures in Tapscript. OP_CAT, by adding a general purpose way to concatenate stack values, would overcome this limitation and greatly increase the functionality of Tapscript.

OP_CAT aims to expand the toolbox of the tapscript developer with a simple, modular, and useful opcode in the spirit of Unix. To demonstrate the usefulness of OP_CAT below we provide a non-exhaustive list of some use cases that OP_CAT would enable:

Bitstream, a protocol for the atomic swap (fair exchange) of bitcoins for decryption keys, that enables decentralized file hosting systems paid in Bitcoin. While such swaps are currently possible on Bitcoin without OP_CAT, they require the use of complex and computationally expensive Verifiable Computation cryptographic techniques. OP_CAT would remove this requirement on Verifiable Computation, making such protocols far more practical to build in Bitcoin.

Tree signatures provide a multisignature script whose size can be logarithmic in the number of public keys and can encode spend conditions beyond n-of-m. For instance a transaction less than 1KB in size could support tree signatures with up to 4,294,967,296 public keys. This also enables generalized logical spend conditions.

Post-Quantum Lamport signatures in Bitcoin transactions. Lamport signatures merely require the ability to hash and concatenate values on the stack. [4] It has been proposed that if ECDSA is broken or a powerful computer was on the horizon, there might be an effort to protect ownership of bitcoins by allowing people to mark their taproot outputs as "script-path only" and then move their coins into such outputs with a leaf in the script tree requiring a Lamport signature. It is an open question if a tapscript commitment would preserve the quantum resistance of Lamport signatures. Beyond this question, the use of Lamport Signatures in taproot outputs is unlikely to be quantum resistant even if the script spend-path is made quantum resistant. This is because taproot outputs can also be spent with a key. An attacker with a sufficiently powerful quantum computer could bypass the taproot script spend-path by finding the discrete log of the taproot output and thus spending the output using the key spend-path. The use of "Nothing Up My Sleeve" (NUMS) points as described in BIP-341 to disable the key spend-path does not disable the key spend-path against a quantum attacker as NUMS relies on the hardness of finding discrete logs. We are not aware of any mechanism which could disable the key spend-path in a taproot output without a soft-fork change to taproot.

Non-equivocation contracts in tapscript provide a mechanism to punish equivocation/double spending in Bitcoin payment channels. OP_CAT enables this by enforcing rules on the spending transaction's nonce. The capability is a useful building block for payment channels and other Bitcoin protocols.

Vaults [6] which are a specialized covenant that allows a user to block a malicious party who has compromised the user's secret key from stealing the funds in that output. As shown in OP_CAT is sufficient to build vaults in Bitcoin.

Replicating CheckSigFromStack which would allow the creation of simple covenants and other advanced contracts without having to pre-sign spending transactions, possibly reducing complexity and the amount of data that needs to be stored. Originally shown to work with Schnorr signatures, this result has been extended to ECDSA signatures.

OP_CAT was available in early versions of Bitcoin. In 2010, a single commit disabled OP_CAT, along with another 15 opcodes. Folklore states that OP_CAT was removed in this commit because it enabled the construction of a script whose evaluation could have memory usage exponential in the size of the script. For example, a script that pushed a 1-byte value on the stack and then repeated the opcodes OP_DUP, OP_CAT 40 times would result in a stack element whose size was greater than 1 terabyte assuming no maximum stack element size. As Bitcoin at that time had a maximum stack element size of 5000 bytes, the effect of this expansion was limited to 5000 bytes. This is no longer an issue because tapscript enforces a maximum stack element size of 520 bytes.”

The last update of the BIP was done on Sep. 8 2024 by Ethan Heilman

### Controversy

The controversy revolves around two main camps:

1. Those who want to preserve Bitcoin’s network for monetary transactions only, arguing that adding smart contract capabilities could introduce risks and complexity.

2. Others who advocate for expanding Bitcoin’s capabilities to support a wider range of applications, seeing OP_CAT as a step towards enhancing the network’s utility.

### Final Thoughts

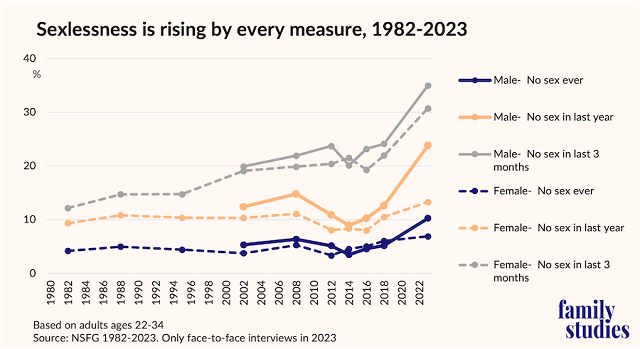

Bitcoin have done what no other asset have done in history, neither gold, its success is clear, and now, that BlackRock is involved, “miraculously”, corporations and governments are getting on board and Bitcoin is not anymore only for criminals or “rat poison” or “is going to zero”.

But as all tech, improvements are important, if those improvements are done to secure more the network and to make it more robust, there will be little to none controversy, however, when those changes are aiming at adding new shinning features that would change Bitcoin into a network with similar features as Ethereum in terms of contracts that requires attention and debate, few questions come to mind:

1. How will that change affect the security of the network?

2. How that change will affect the blockchain usage?

3. What is the projected impact over the fees per transaction if this change is approved?

4. Will the impact create pressure for the block size increase discussion to come back to the table and with it a second war?

Looking into Ethan Heilman work and contribution to the Bitcoin ecosystem, I am inclined to believe that he has considered most of those questions.

Looking forward to observe the evolution of this proposal.

#### You liked the article? Make my day brighter!

Like and share!

Last but not least, the following link is an unstoppable domain, it will open a page in which you can perform an anonymous contribution to support my work:

[https://rodswallet.unstoppable/](https://rodswallet.unstoppable/)

The link didn’t open?

To open the link you need to use a best in class browser that supports web3, two are recommended: Brave Browser and Opera Browser

-

@ f33c8a96:5ec6f741

2025-01-22 20:38:02

<div style="position:relative;padding-bottom:56.25%;height:0;overflow:hidden;max-width:100%;"><iframe src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/V-7u7bJccSM?enablejsapi=1" style="position:absolute;top:0;left:0;width:100%;height:100%;border:0;" allowfullscreen></iframe></div>

-

@ bf47c19e:c3d2573b

2025-01-22 19:14:55

###### [PREUZMITE ODLOMAK](https://www.knjizare-vulkan.rs/files/files/pdf/317878.pdf)

###### [KUPITE ELEKTRONSKO IZDANJE KNJIGE](https://delfi.rs/eknjiga/120661_delfi_knjizare.html?priceDisplayType=eBook)

###### Autor: Natanijel Poper

###### Prevodilac: Nevena Andrić

---

Kako funkcioniše novac, ko iz njega izvlači korist i kako bi sve to moglo izgledati ubuduće.

Bitkoin, revolucionarna digitalna valuta i finansijska tehnologija, predstavlja začetak jednog globalnog društvenog pokreta utopijskih stremljenja. Ideja nove valute, koju održavaju personalni računari širom sveta, bila je predmet brojnih šala, ali to je nije sprečilo da preraste u tehnologiju vrednu više milijardi dolara, tehnologiju s mnoštvom sledbenika, koji je smatraju najvažnijim novim izumom još od stvaranja interneta.

Poklonici bitkoina, od Pekinga do Buenos Ajresa, u njemu vide mogućnost postojanja finansijskog sistema bez uticaja vlade ili banaka, novu globalnu valutu digitalne ere. Digitalno zlato je neobična priča o jednom grupnom izumu, pripovest o ličnostima koje su stvorile bitkoin, uključujući i jednog finskog studenta, argentinskog milionera, kineskog preduzetnika, Tajlera i Kamerona Vinklvosa, tajanstvenog tvorca bitkoina Satošija Nakamota, kao i Rosa Ulbrihta, osnivača Silk rouda, tržišta narkotika na internetu.

„Sjajna priča. Bitkoin će preobraziti i finansijski svet i našu upotrebu interneta, a ova izuzetno zanimljiva knjiga predstavlja hroniku njegovog neverovatnog nastanka. Poperova priča se ne ispušta iz ruke, puna je živopisnih izumitelja, i predstavlja ključno štivo za svakoga ko želi da razume budućnost.“ Volter Ajzakson, autor knjige Stiv Džobs

„Bitkoin je možda tekovina informatičkih nauka, ali priča o njemu je priča o ljudima. Ovaj nadasve zabavan istorijat podseća nas da istina može biti čudnija od književnosti, i ponekad je spektar stvarnih ličnosti još neobičniji i zanimljiviji od književnih.“ Lari Samers, bivši ministar finansija SAD

[Trejler za knjigu "Digitalno zlato" Natanijela Popera](https://youtu.be/_W2ITkRY9mY)

-

@ 5d4b6c8d:8a1c1ee3

2025-01-22 19:06:48

This isn't a fully crystalized post, but I want to see what people think about egregiously bad officiating in an era of widespread sports betting.

It seems so obvious that Chiefs games, for instance, are rigged. I don't think that's specifically done for gambling reasons. My gut says it has more to do with marketing and league revenue.

Might the sportsbooks be a check on this corruption of the sport, since honest matches (or at least the perception of such) are in their interest? People don't like betting on rigged events, after all.

In other cases, though, atrocious calls can no longer live in a vacuum. We, as spectators, are now always wondering if officials are putting their thumbs on the scales for their own enrichment.

If people keep watching and buying up all the merch, though, is there any incentive for the league to address it?

If the leagues were to attempt to address it, what's the best way to impose accountability?

originally posted at https://stacker.news/items/860390

-

@ bf47c19e:c3d2573b

2025-01-22 18:55:17

Originalni tekst na [dvadesetjedan.com](https://dvadesetjedan.com/blog/btc-scenarij-uspijeha)

###### Autor: Vijay Boyapati / Prevod na hrvatski: [Matija](t.me/matijap9)

---

Sa zadnjim cijenama koje je bitcoin dosegao 2017., optimističan scenarij za ulagače se možda čini toliko očitim da ga nije potrebno niti spominjati. Alternativno, možda se nekome čini glupo ulagati u digitalnu vrijednost koja ne počiva na nijednom fizičkom dobru ili vladi i čiji porast cijene su neki usporedili sa manijom tulipana ili dot-com balonom. Nijedno nije točno; optimističan scenarij za Bitcoin je uvjerljiv, ali ne i očit. Postoje značajni rizici kod ulaganja u Bitcoin, no, kao što planiram pokazati, postoji i ogromna prilika.

#### Geneza

Nikad u povijesti svijeta nije bilo moguće napraviti transfer vrijednosti među fizički udaljenim ljudima bez posrednika, poput banke ili vlade. 2008. godine, anonimni Satoshi Nakamoto je objavio [8 stranica rješenja](https://bitcoin.org/files/bitcoin-paper/bitcoin_hr.pdf) na dugo nerješivi računalski problem poznat kao “Problem Bizantskog Generala.” Njegovo rješenje i sustav koji je izgradio - Bitcoin - dozvolio je, prvi put ikad, da se vrijednost prenosi brzo i daleko, bez ikakvih posrednika ili povjerenja. Implikacije kreacije Bitcoina su toliko duboke, ekonomski i računalski, da bi Nakamoto trebao biti prva osoba nominirana za Nobelovu nagradu za ekonomiju i Turingovu nagradu.

Za ulagače, važna činjenica izuma Bitcoina (mreže i protokola) je stvaranje novog oskudnog digitalnog dobra - bitcoina (monetarne jedinice). Bitcoini su prenosivi digitalni “novčići” (tokeni), proizvedeni na Bitcoin mreži kroz proces nazvan “rudarenje” (mining). Rudarenje Bitcoina je ugrubo usporedivo sa rudarenjem zlata, uz bitnu razliku da proizvodnja bitcoina prati unaprijed osmišljeni i predvidivi raspored. Samo 21 milijun bitcoina će ikad postojati, i većina (2017., kada je ovaj tekst napisan) su već izrudareni. Svake četiri godine, količina rudarenih bitcoina se prepolovi. Produkcija novih bitcoina će potpuno prestati 2140. godine.

*Stopa inflacije —— Monetarna baza*

Bitcoine ne podržava nikakva roba ili dobra, niti ih garantira ikakva vlada ili firma, što postavlja očito pitanje za svakog novog bitcoin ulagača: zašto imaju uopće ikakvu vrijednost? Za razliku od dionica, obveznica, nekretnina ili robe poput nafte i žita, bitcoine nije moguće vrednovati koristeći standardne ekonomske analize ili korisnost u proizvodnji drugih dobara. Bitcoini pripadaju sasvim drugoj kategoriji dobara - monetarnih dobara, čija se vrijednost definira kroz tzv. teoriju igara; svaki sudionik na tržištu vrednuje neko dobro, onoliko koliko procjenjuje da će ga drugi sudionici vrednovati. Kako bismo bolje razumjeli ovo svojstvo monetarnih dobara, trebamo istražiti podrijetlo novca.

#### Podrijetlo novca

U prvim ljudskim društvima, trgovina među grupama se vršila kroz robnu razmjenu. Velika neefikasnost prisutna u robnoj razmjeni je drastično ograničavala količinu i geografski prostor na kojem je bila moguća. Jedan od najvećih problema sa robnom razmjenom je problem dvostruke podudarnosti potražnje. Uzgajivač jabuka možda želi trgovati sa ribarom, ali ako ribar ne želi jabuke u istom trenutku, razmjena se neće dogoditi. Kroz vrijeme, ljudi su razvili želju za čuvanjem određenih predmeta zbog njihove rijetkosti i simbolične vrijednosti (npr. školjke, životinjski zube, kremen). Zaista, kako i Nick Szabo govori u svojem izvrsnom [eseju o podrijetlu novca](https://nakamotoinstitute.org/shelling-out/), ljudska želja za sakupljanjem predmeta pružila je izraženu evolucijsku prednost ranom čovjeku nad njegovim najbližim biološkim rivalom, neandertalcem - Homo neanderthalensis.

> "Primarna i najbitnija evolucijska funkcija sakupljanja bila je osigurati medij za čuvanje i prenošenje vrijednosti".

Predmeti koje su ljudi sakupljali služili su kao svojevrsni “proto-novac,” tako što su omogućavale trgovinu među antagonističkim plemenima i dozvoljavale bogatsvu da se prenosi na sljedeću generaciju. Trgovina i transfer takvih predmeta bile su rijetke u paleolitskim društvima, te su oni služili više kao “spremište vrijednosti” (store of value) nego kao “medij razmjene” (medium of exchange), što je uloga koju danas igra moderni novac. Szabo objašnjava:

> "U usporedbi sa modernim novcem, primitivan novac je imao jako malo “brzinu” - mogao je promijeniti ruke samo nekoliko puta u životu prosječnog čovjeka. Svejedno, trajni i čvrsti sakupljački predmet, što bismo danas nazvali “nasljeđe,” mogao je opstati mnogo generacija, dodajući znatnu vrijednost pri svakom transferu - i zapravo omogućiti transfer uopće".

Rani čovjek suočio se sa bitnom dilemom u teoriji igara, kada je odlučivao koje predmete sakupljati: koje od njih će drugi ljudi željeti? Onaj koji bi to točno predvidio imao bi ogromnu prednost u mogućnosti trgovine i akvizicije bogatsva. Neka američka indijanska plemena, npr. Naraganseti, specijalizirala su se u proizvodnji sakupljačkih dobara koja nisu imala drugu svrhu osim trgovine. Valja spomenuti da što je ranije predviđanje da će neko dobro imati takvu vrijednost, veća je prednost koju će imati onaj koji je posjeduje, zato što ju je moguće nabaviti jeftinije, prije nego postane vrlo tražena roba i njezona vrijednost naraste zajedno sa populacijom. Nadalje, nabava nekog dobra u nadi da će u budućnosti biti korišteno kao spremište vrijednosti, ubrzava upravo tu primjenu. Ova cirkularnost je zapravo povratna veza (feedback loop) koja potiče društva da se rapidno slože oko jednog spremišta vrijednosti. U terminima teorije igara, ovo je znano kao “[Nashov ekvilibrij](https://sh.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nashov_ekvilibrijum).” Postizanje Nashovog ekvilibrija za neko spremište vrijednosti je veliko postignuće za društvo, pošto ono znatno olakšava trgovinu i podjelu rada, i time omogućava napredak civilizacije.

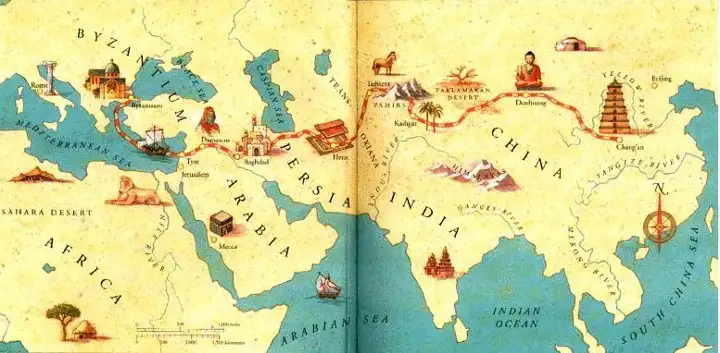

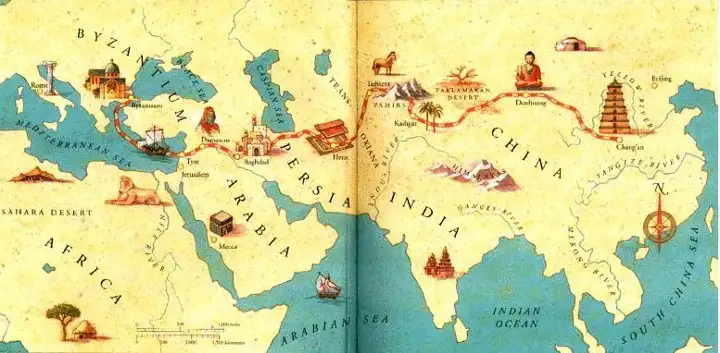

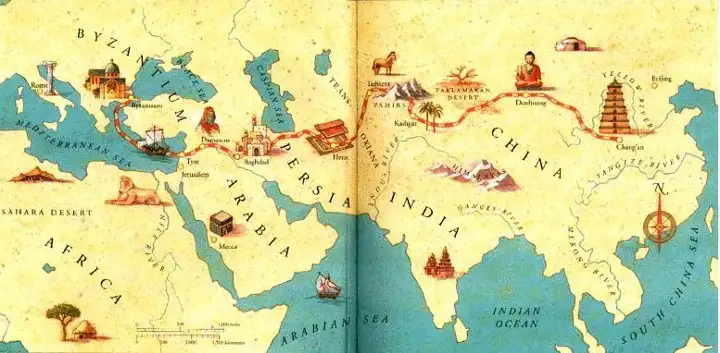

Tisućljećima, kako su ljudska društva rasla i otvarala trgovinske puteve, različite aplikacije spremišta vrijednosti u individualnim društvima počele su se natjecati međusobno. Trgovci su imali izbor: čuvati svoju zaradu u spremištu vrijednosti vlastite kulture, ili one kulture sa kojom su trgovali, ili mješavini oboje. Benefit štednje u stranom spremištu vrijednosti bila je uvećana sposobnost trgovanja u povezanom stranom društvu. Trgovci koji su štedili u stranom spremištu vrijednosti su također imali dobrih razloga da potiču svoje društvo da ga prihvati, jer bi tako uvećali vrijednost vlastite ušteđevine. Prednosti “uvezene” tehnologije spremanja vrijednosti bile su prisutne ne samo za trgovce, nego i za sama društva. Kada bi se dvije grupe konvergirale u jedinstvenom spremištu vrijednosti, to bi značajno smanjilo cijenu troškova trgovine jednog s drugim, i samim time povećanje bogatstva kroz trgovinu. I zaista, 19. stoljeće bilo je prvi put da je najveći dio svijeta prihvatio jedinstveno spremište vrijednosti - zlato - i u tom periodu vidio najveću eksploziju trgovine u povijesti svijeta. O ovom mirnom periodu, pisao je John Maynard Keynes:

> "Kakva nevjerojatna epizoda u ekonomskom napretku čovjeka… za svakog čovjeka iole iznadprosječnog, iz srednje ili više klase, život je nudio obilje, ugodu i mogućnosti, po niskoj cijeni i bez puno problema, više nego monarsima iz prethodnih perioda. Stanovnik Londona mogao je, ispijajući jutarnji čaj iz kreveta, telefonski naručiti razne proizvode iz cijele Zemlje, u količinama koje je želio, i sa dobrim razlogom očekivati njihovu dostavu na svoj kućni prag."

#### Svojstva dobrog spremišta vrijednosti

Kada se spremišta vrijednosti natječu jedno s drugim, specifična svojstva rade razliku koja daje jednom prednost nad drugim. Premda su mnoga dobra u prošlosti korištena kao spremišta vrijednosti ili kao “proto-novac,” određena svojstva su se pokazala kao posebno važna, i omogućila dobrima sa njima da pobijede. Idealno spremište vrijednosti biti će:

* **Trajno**: dobro ne smije biti kvarljivo ili lako uništeno. Tako naprimjer, žito nije idealno spremište vrijednosti.

* **Prenosivo**: dobro mora biti lako transportirati i čuvati, što omogućuje osiguranje protiv gubitka ili krađe i dopušta trgovinu na velike udaljenosti. Tako, krava je lošije spremište vrijednosti od zlatne narukvice.

* **Zamjenjivo**: jedna jedinica dobra treba biti zamjenjiva sa drugom. Bez zamjenjivosti, problem podudarnosti želja ostaje nerješiv. Time, zlato je bolje od dijamanata, jer su oni nepravilni u obliku i kvaliteti.

* **Provjerljivo**: dobro mora biti lako i brzo identificirano i testirano za autentičnost. Laka provjera povećava povjerenje u trgovini i vjerojatnost da će razmjena biti dovršena.

* **Djeljivo**: dobro mora biti lako djeljivo na manje dijelove. Premda je ovo svojstvo bilo manje važno u ranim društvima gdje je trgovina bila rijetka, postalo je važnije sa procvatom trgovine. Količine koje su se mijenjale postale su manje i preciznije.

* **Oskudno**: Monetarno dobro mora imati “cijenu nemoguću za lažirati,” kao što je rekao Nick Szabo. Drugim riječima, dobro ne smije biti obilno ili lako dostupno kroz proizvodnju. Oskudnost je možda i najvažnije svojstvo spremišta vrijednosti, pošto se izravno vezuje na ljudsku želju da sakupljamo ono što je rijetko. Ona je izvor vrijednosti u spremištu vrijednosti.

* **Duge povijesti**: što je dulje neko dobro vrijedno za društvo, veća je vjerojatnost da će biti prihvaćeno kao spremište vrijednosti. Dugo postojeće spremište vrijednosti biti će jako teško uklonjeno od strane došljaka, osim u slučaju sile (ratno osvajanje) ili ako je nova tehnologija znatno bolja u ostalim svojstvima.

* **Otporno na cenzuru**: novije svojstvo, sve više važno u modernom digitalnom svijetu sa sveprisutnim nadzorom, je otpornost na cenzuru. Drugim riječima, koliko je teško da vanjski agent, kao korporacija ili država, spriječi vlasnika dobra da ga čuva i koristi. Dobra koja su otporna na cenzuru su idealna za ljude koji žive u režimima koji prisilno nadziru kapital ili čine neke oblike mirne trgovine protuzakonitima.

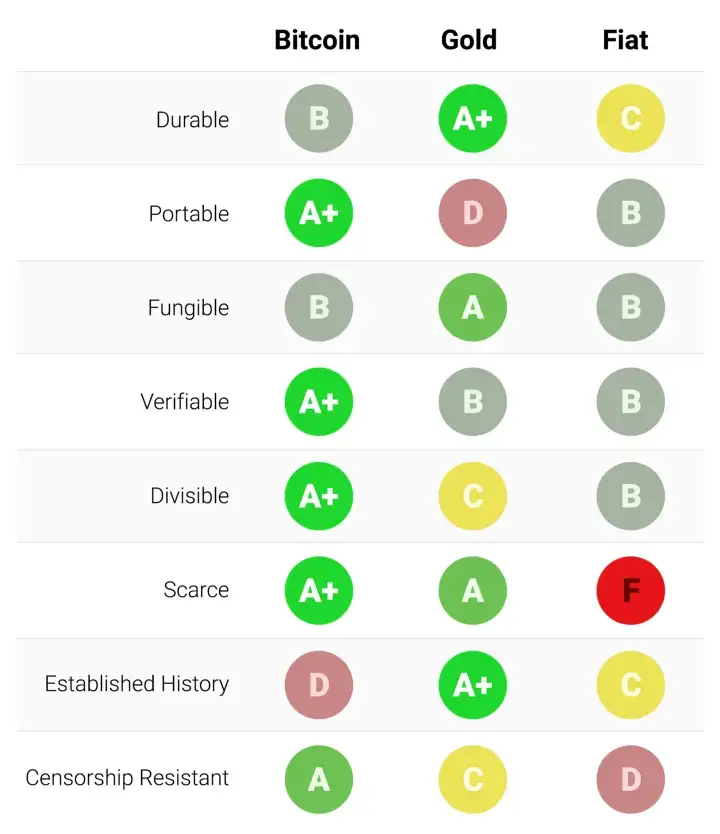

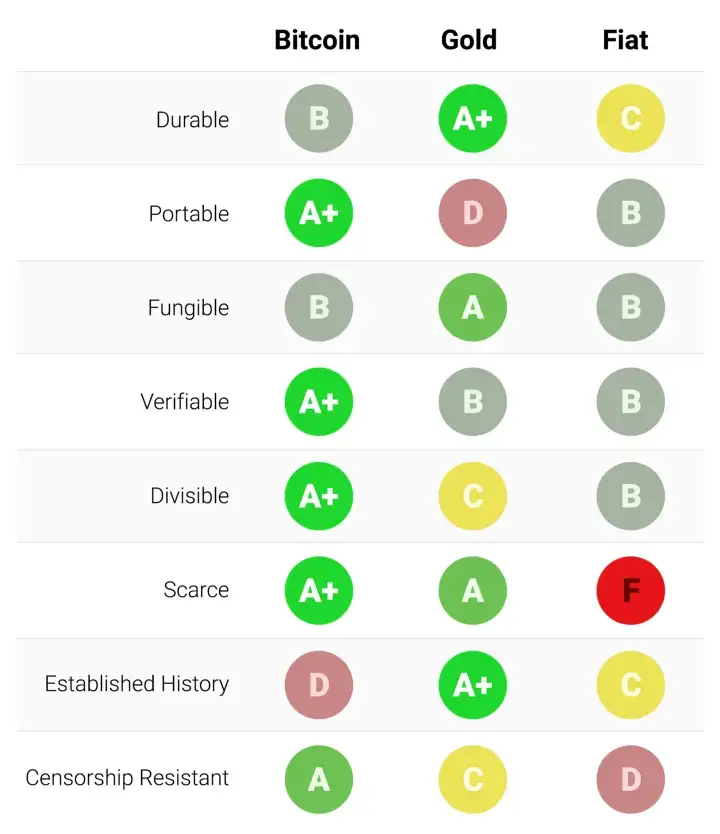

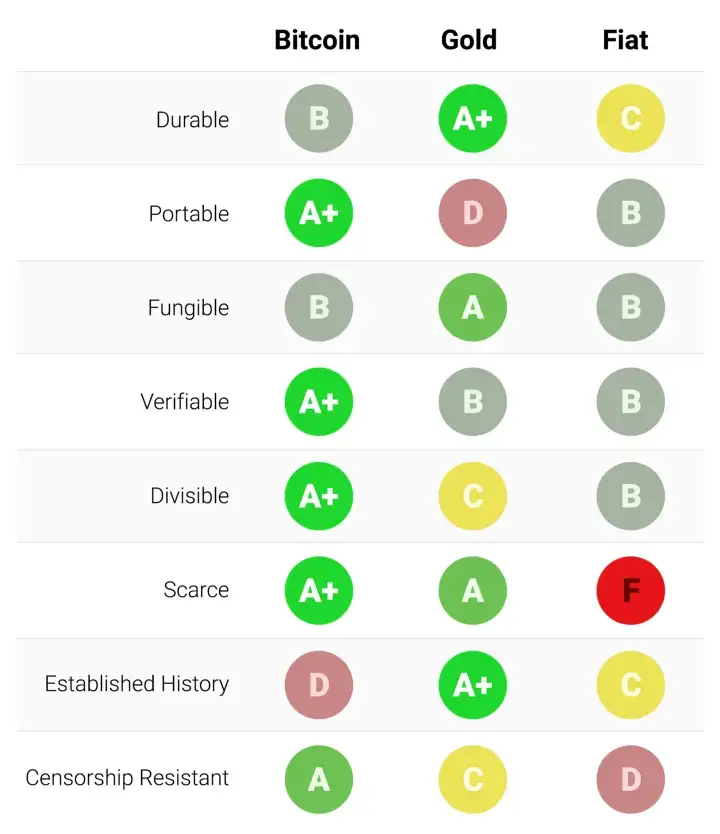

Ova tablica ocjenjuje Bitcoin, zlato (gold) i fiat novac (kao što je euro ili dolar) po svojstvima izlistanim gore. Objašnjenje svake ocjene slijedi nakon tablice.

###### Trajnost:

Zlato je neosporeni kralj trajnosti. Velika većina zlata pronađenog kroz povijest, uključujući ono egipatskih faraona, opstaje i danas i vjerojatno će postojati i za tisuću godina. Zlatnici korišteni u antičko doba imaju značajnu vrijednost i danas. Fiat valute i bitcoini su digitalni zapisi koji ponekad imaju fizički oblik (npr. novčanice). Dakle, njihovu trajnost ne određuju njihova fizička svojstva (moguće je zamijeniti staru i oštećenu novčanicu za novu), nego institucije koje stoje iza njih. U slučaju fiat valuta, mnoge države su nastale i nestale kroz stoljeća, i valute su nestale s njima. Marke iz Weimarske republike danas nemaju vrijednost zato što institucija koja ih je izdavala više ne postoji. Ako je povijest ikakav pokazatelj, ne bi bilo mudro smatrati fiat valute trajnima dugoročno; američki dolar i britanska funta su relativne anomalije u ovom pogledu. Bitcoini, zato što nemaju instituciju koja ih održava, mogu se smatrati trajnima dok god mreža koja ih osigurava postoji. Obzirom da je Bitcoin još uvijek mlada valuta, prerano je za čvrste zaključke o njegovoj trajnosti. No, postoje ohrabrujući znakovi - prominente države su ga pokušavale regulirati, hakeri ga napadali - usprkos tome, mreža nastavlja funkcionirati, pokazujući visok stupanj antifragilnosti.

###### Prenosivost:

Bitcoini su najprenosivije spremište vrijednosti ikad. Privatni ključevi koji predstavljaju stotine milijuna dolara mogu se spremiti na USB drive i lako ponijeti bilo gdje. Nadalje, jednako velike sume mogu se poslati na drugi kraj svijeta skoro instantno. Fiat valute, zbog svojeg temeljno digitalnog oblika, su također lako prenosive. Ali, regulacije i kontrola kapitala od strane države mogu ugroziti velike prijenose vrijednosti, ili ih usporiti danima. Gotovina se može koristiti kako bi se izbjegle kontrole kapitala, ali onda rastu rizik čuvanja i cijena transporta. Zlato, zbog svojeg fizičkog oblika i velike gustoće, je najmanje prenosivo. Nije čudo da većina zlatnika i poluga nikad ne napuste sefove. Kada se radi prijenos zlata između prodavača i kupca, uglavnom se prenosi samo ugovor o vlasništvu, ne samo fizičko zlato. Prijenos fizičkog zlata na velike udaljenosti je skupo, riskantno i sporo.

###### Zamjenjivost:

Zlato nam daje standard za zamjenjivost. Kada je rastopljeno, gram zlata je praktički nemoguće razlikovati od bilo kojeg drugog grama, i zlato je oduvijek bilo takvo. S druge strane, fiat valute, su zamjenjive samo onoliko koliko njihova institucija želi da budu. Iako je uglavnom slučaj da je novčanica zamjenjiva za drugu istog iznosa, postoje situacije u kojima su velike novčanice tretirane drukčije od malih. Naprimjer, vlada Indije je, u pokušaju da uništi neoporezivo sivo tržište, potpuno oduzela vrijednost novčanicama od 500 i 1000 rupija. To je uzrokovalo da ljudi manje vrednuju te novčanice u trgovini, što je značilo da više nisu bile zaista zamjenjive za manje novčanice. Bitcoini su zamjenjivi na razini mreže; svaki bitcoin je pri prijenosu tretiran kao svaki drugi. No, zato što je moguće pratiti individualne bitcoine na blockchainu, određeni bitcoin može, u teoriji, postati “prljav” zbog korštenja u ilegalnoj trgovini, te ga trgovci ili mjenjačnice možda neće htjeti prihvatiti. Bez dodatnih poboljšanja oko privatnosti i anonimnosti na razini mrežnog protokola, bitcoine ne možemo smatrati jednako zamjenjivim kao zlato.

###### Mogućnost provjere:

Praktično gledajući, autentičnost fiat valuta i zlata je prilično lako provjeriti. Svejedno, i usprkos pokušajima da spriječe krivotvorenje novčanica, i dalje postoji potencijal prevare za vlade i njihove građane. Zlato također nije imuno na krivotvorenje. Sofisticirani kriminalci su koristili [pozlaćeni tungsten](https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/fake-gold-wafer-rbc-canadian-mint-1.4368801) kako bi prevarili kupce zlata. Bitcoine je moguće provjeriti sa matematičkom sigurnošću. Korištenjem kriptografskih potpisa, vlasnik bitcoina može javno demonstrirati da posjeduje bitcoine koje tvrdi da posjeduje.

###### Djeljivost:

Bitcoine je moguće podijeliti u stotinu milijuna manjih jedinica (zvanih satoshi), i prenositi takve (no, valja uzeti u obzir ekonomičnost prijenosa malih iznosa, zbog cijene osiguravanja mreže - “network fee”). Fiat valute su tipično dovoljno djeljive na jedinice sa vrlo niskom kupovnom moći. Zlato, iako fizički i teoretski djeljivo, postaje teško za korištenje kada se podijeli na dovoljno male količine da bi se moglo koristiti u svakodnevnoj trgovini.

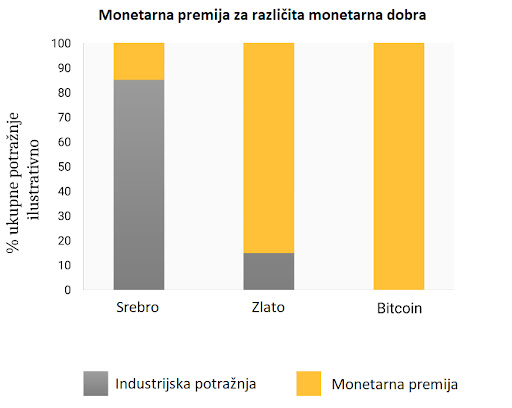

###### Oskudnost:

Svojstvo koje najjasnije razlikuje Bitcoin od fiat valuta i zlata je njegova unaprijed definirana oskudnost. Od početka, konačna količina bitcoina nikad neće biti veća od 21 milijun. To daje vlasnicima bitcoina jasan i znan uvid u postotak ukupnog vlasništva. Naprimjer, vlasnik 10 bitcoina bi znao da najviše 2,1 milijuna ljudi (manje od 0.03% populacije) može ikad imati isto bitcoina kao i on. Premda je kroz povijest uvijek bilo oskudno, zlato nije imuno na povećanje ukupne količine. Ako se ikad izumi nova, ekonomičnija metoda rudarenja ili proizvodnje zlata, ukupna količina zlata bi se mogla dramatično povećati (npr. [rudarenje morskog dna](https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2016/07/deep-sea-mining-five-facts/) ili [asteroida](http://web.mit.edu/12.000/www/m2016/finalwebsite/solutions/asteroids.html)). Na kraju, fiat valute, relativno nov izum u povijesti, pokazale su se sklonima konstantnim povećanjima u količini. Države su pokazale stalnu sklonost inflaciji monetarne kvantitete kako bi rješavale kratkoročne političke probleme. Inflacijske tendencije vlada diljem svijeta čine fiat valute gotovo sigurnim da će gubiti vrijednost kroz vrijeme.

###### Etablirana povijest:

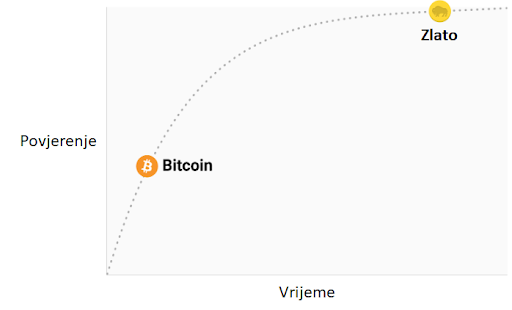

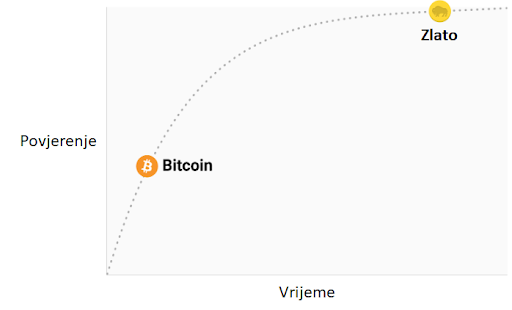

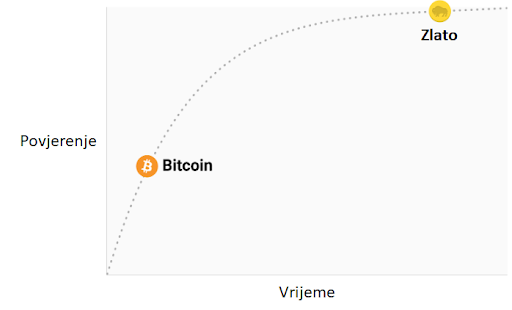

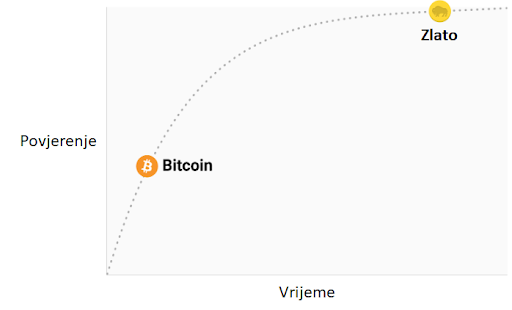

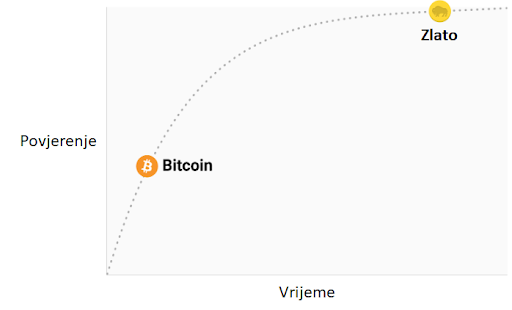

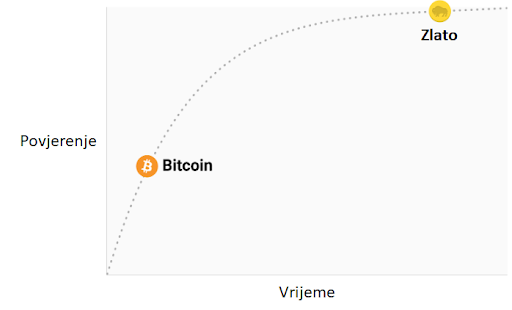

Nijedno monetarno dobro nema povijest kao zlato, koje je imalo vrijednost za cijelog trajanja ljudske civilizacije. Kovanice izrađene u antičko doba i [danas imaju značajnu vrijednost](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hoxne_Hoard). Ne može se isto reći za fiat valute, koje su same relativno nova povijesna anomalija. Od njihovog početka, fiat valute su imale gotovo univerzalni smjer prema bezvrijednosti. Korištenje inflacije kao podmuklog načina za nevidljivo oporezivanje građana je vječita kušnja kojoj se skoro nijedna država u povijesti nije mogla oduprijeti. Ako je 20. stoljeće, u kojem je fiat novac dominirao globalni monetarni poredak, demonstriralo neku ekonomsku istinu, to je onda bila ta da ne možemo računati na fiat novac da održi vrijednost u dužem ili srednjem vremenskom periodu. Bitcoin, usprkos svojoj novosti, je preživio dovoljno testova tržišta da postoji velika vjerojatnost da neće nestati kao vrijedno dobro. Nadalje, [Lindy efekt](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lindy_effect) govori da što duže Bitcoin bude korišten, to će veća biti vjera u njega i njegovu sposobnost da nastavi postojati dugo u budućnost. Drugim riječima, društvena vjera u monetarno dobro je asimptotička, kao u grafu ispod:

Ako Bitcoin preživi prvih 20 godina, imat će gotovo sveopće povjerenje da će trajati zauvijek, kao što ljudi vjeruju da je internet trajna stvar u modernom svijetu.

###### Otpor na cenzuru

Jedan od najbitnijih izvora za ranu potražnju bitcoina bila je njegova upotreba u ilegalnoj kupovini i prodaji droge. Mnogi su zato pogrešno zaključili da je primarna potražnja za bitcoinima utemeljena u njihovoj prividnoj anonimnosti. Međutim, Bitcoin nije anonimna valuta; svaka transakcija na mreži je zauvijek zapisana na javnom blockchainu. Povijesni zapis transakcija dozvoljava forenzičkoj analizi da identificira izvore i tijek sredstava. [Takva analiza](http://blog.wizsec.jp/2017/07/breaking-open-mtgox-1.html) dovela je do uhićenja počinitelja zloglasne MtGox pljačke. Premda je istina da dovoljno oprezna i pedantna osoba može sakriti svoj identitet koristeći Bitcoin, to nije razlog zašto je Bitcoin bio toliko popularan u trgovini drogom.

Ključno svojstvo koje čini Bitcoin najboljim za takve aktivnosti je njegova agnostičnost i nepotrebnost za dozvolom (“premissionlessness”) na mrežnoj razini. Kada se bitcoini prenose na Bitcoin mreži, ne postoji nitko tko dopušta transakcije. Bitcoin je distribuirana peer-to-peer (korisnik-korisniku) mreža, i samim time dizajnirana da bude otporna na cenzuru. Ovo je u velikom kontrastu sa fiat bankarskim sustavom, u kojem države reguliraju banke i ostale institucije prijenosa novca, kako bi one prijavljivale i sprječavale protuzakonito korištenje monetarnih dobara. Klasičan primjer regulacije novca su kontrole kapitala. Npr., bogati milijunaš će vrlo teško prenijeti svoje bogatstvo u novu zemlju, kada bježi iz opresivnog režima. Premda zlato nije izdano i proizvedeno od države, njegova fizička priroda ga čini teško prenosivim kroz prostor, i samim time ga je daleko lakše regulirati nego Bitcoin. Indijski [Akt kontrole zlata](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Gold_(Control)_Act,_1968) je primjer takve regulacije.

Bitcoin je odličan u većini gore navedenih svojstava, što mu omogućava da bude marginalno bolji od modernih i drevnih monetarnih dobara, te da pruži poticaje za svoje rastuće društveno usvajanje. Specifično, moćna kombinacija otpornosti na cenzuru i apsolutne oskudnosti bila je velika motivacija za bogate ulagače koji su uložili dio svojeg bogatstva u Bitcoin.

#### Evolucija novca

U modernoj monetarnoj ekonomiji postoji opsesija sa ulogom novca kao medija razmjene. U 20. stoljeću, države su monopolizirale izdavanje i kontrolu novca i kontinuirano potkopavale njegovo svojstvo spremišta vrijednosti, stvarajući lažno uvjerenje da je primarna svrha novca biti medij razmjene. Mnogi su kritizirali Bitcoin, govoreći da je neprikladan da bude novac zato što mu je cijena bila previše volatilna za medij razmjene. No, novac je uvijek evoluirao kroz etape; uloga spremišta vrijednosti je dolazila prije medija razmjene. Jedan od očeva marginalističke ekonomije, William Stanley Jevons, objašnjava:

> "Povijesno govoreći… čini se da je zlato prvo služilo kao luksuzni metal za ukras; drugo, kao sačuvana vrijednost; treće, kao medij razmjene; i konačno, kao mjerilo vrijednosti."

U modernoj terminologiji, novac uvijek evoluira kroz četiri stadija:

1. **Kolekcionarstvo**: U prvoj fazi svoje evolucije, novac je tražen samo zbog svojih posebnih svojstava, uglavnom zbog želja onog koji ga posjeduje. Školjke, perlice i zlato su bili sakupljani prije nego su poprimili poznatije uloge novca.

2. **Spremište vrijednosti**: Jednom kada je novac tražen od dovoljnog broja ljudi, biti će prepoznat kao način za čuvanje i spremanje vrijednosti kroz vrijeme. Kada neko dobro postane široko korišteno kao spremište vrijednosti, njegova kupovna moć raste sa povećanom potražnjom za tu svrhu. Kupovna moć spremišta vrijednosti će u jednom trenutku doći do vrhunca, kada je dovolno rašireno i broj novih ljudi koji ga potražuju splasne.

3. **Sredstvo razmjene**: Kada je novac potpuno etabliran kao spremište vrijednosti, njegova kupovna moć se stabilizira. Nakon toga, postane prikladno sredstvo razmjene zbog stabilnosti svoje cijene. U najranijim danima Bitcoina, mnogi ljudi nisu shvaćali koju buduću cijenu plaćaju koristeći bitcoine kao sredstvo razmjene, umjesto kao novonastalo spremište vrijednosti. Poznata priča o čovjeku koji je za 10,000 bitcoina (vrijednih oko 94 milijuna dolara kada je ovaj članak napisan) za dvije pizze ilustrira ovaj problem.

4. **Jedinica računanja vrijednosti**: Jednom kada je novac široko korišten kao sredstvo razmjene, dobra će biti vrednovana u njemu, tj. većina cijena će biti izražena u njemu. Uobičajena zabluda je da je većinu dobara moguće zamijeniti za bitcoine danas. Npr., premda je možda moguće kupiti šalicu kave za bitcoine, izlistana cijena nije prava bitcoin cijena; zapravo se radi o cijeni u državnoj valuti koju želi trgovac, preračunatu u bitcoin po trenutnoj tržišnoj cijeni. Kad bi cijena bitcoina pala u odnosu na valutu, vrijednost šalice izražena u bitcoinima bi se povećala. Od trenutka kada trgovci budu voljni prihvaćani bitcoine kao platežno sredstvo, bez obraćanja pažnje na vrijednost bitcoina u državnoj fiat valuti, moći ćemo reći da je Bitcoin zaista postao jedinica računanja vrijednosti.

Monetarna dobra koja još nisu jedinice računanja vrijednosti možemo smatrati “djelomično monetiziranima.” Danas zlato ima takvu ulogu, jer je spremište vrijednosti, ali su mu uloge sredstva razmjene i računanja vrijednosti oduzete intervencijama država. Moguće je također da se jedno dobro koristi kao sredstvo razmjene, dok druga ispunjavaju ostale uloge. To je tipično u zemljama gdje je država disfunkcionalna, npr. Argentina ili Zimbabwe. U svojoj knjizi, Digitalno zlato, Nathaniel Popper piše:

> "U Americi, dolar služi trima funkcijama novca: nudi sredstvo razmjene, jedinicu za mjerenje vrijednosti dobara, i mjesto gdje se može čuvati vrijednosti. S druge strane, argentinski peso je korišten kao sredstvo razmjene (za svakodnevne potrebe), ali ga nitko nije koristio kao spremište vrijednosti. Štednja u pesosima bila je ekvivalent bacanja novca. Zato su ljudi svu svoju štednju imali u dolarima, jer je dolar bolje čuvao vrijednost. Zbog volatilnosti pesosa, ljudi su računali cijene u dolarima, što im je pružalo pouzdaniju jedinicu mjerenja kroz vrijeme."

Bitcoin je trenutno u fazi tranzicije iz prvog stadija monetizacije u drugi. Vjerojatno će proći nekoliko godina prije nego Bitcoin pređe iz začetaka spremišta vrijednosti u istinski medij razmjene, i put do tog trenutka je još uvijek pun rizika i nesigurnosti. Važno je napomenuti da je ista tranzicija trajala mnogo stoljeća za zlato. Nitko danas živ nije doživio monetizaciju dobra u realnom vremenu (kroz koju Bitcoin prolazi), tako da nemamo puno iskustva govoriti o putu i načinu na koji će se monetizacija dogoditi.

#### Put monetizacije

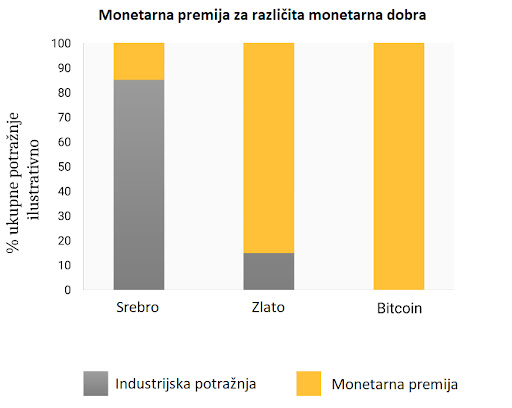

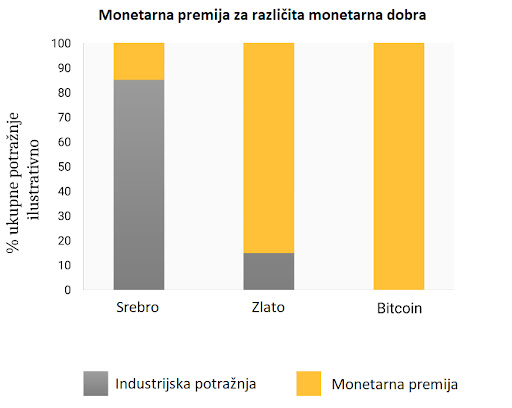

Kroz proces monetizacije, monetarno dobro će naglo porasti u kupovnoj moći. Mnogi su tako komentirali da je uvećanje kupovne moći Bitcoina izgledalo kao “balon” (bubble). Premda je ovaj termin često korišten kako bi ukazao na pretjeranu vrijednosti Bitcoina, sasvim slučajno je prikladan. Svojstvo koje je uobičajeno za sva monetarna dobra jest da je njihova kupovna moć viša nego što se može opravdati samo kroz njihovu uporabnu vrijednost. Zaista, mnogi povijesni novci nisu imali uporabnu vrijednost. Razliku između kupovne moći i vrijednosti razmjene koju bi novac mogao imati za svoju inherentnu korisnost, možemo razmatrati kao “monetarnu premiju.” Kako monetarno dobro prolazi kroz stadije monetizacije (navedene gore), monetarna premija raste. No, ta premija ne raste u ravnoj i predvidivoj liniji. Dobro X, koje je bilo u procesu monetizacije, može izgubiti u usporedbi sa dobrom Y koje ima više svojstava novca, te monetarna premija dobra X drastično padne ili potpuno nestane. Monetarna premija srebra je skoro potpuno nestala u kasnom 19. stoljeću, kada su ga vlade diljem svijeta zamijenile zlatom kao novcem.

Čak i u odsustvu vanjskih faktora, kao što su intervencije vlade ili druga monetarna dobra, monetarna premija novog novca neće ići predvidivim putem. Ekonomist [Larry White](http://oll.libertyfund.org/pages/misestmc) primijetio je:

> "problem sa pričom “balona,” naravno, je da je ona konzistentna sa svakim putem cijene, i time ne daje ikakvo objašnjenje za specifičan put cijene"

Proces monetizacije opisuje teorija igara; svaki akter na tržištu pokušava predvidjeti agregiranu potražnju ostalih aktera, i time buduću monetarnu premiju. Zato što je monetarna premija nevezana za inherentnu korisnost, tržišni akteri se uglavnom vode za prošlim cijenama da bi odredili je li neko dobro jeftino ili skupo, i žele li ga kupiti ili prodati. Veza trenutne potražnje sa prošlim cijenama naziva se “ovisnost o putu” (path dependence); ona je možda najveći izvor konfuzije u shvaćanju kretanja cijena monetarnih dobara.

Kada kupovna moć monetarnog dobra naraste zbog većeg i šireg korištenja, očekivanja tržišta o definicijama “jeftinog” i “skupog” se mijenjaju u skladu s time. Slično tome, kada cijena monetarnog dobra padne, očekivanja tržišta mogu se promijeniti u opće vjerovanje da su prethodne cijene bile “iracionalne” ili prenapuhane. Ovisnost o putu novca ilustrirana je [riječima ](http://thereformedbroker.com/2017/09/11/you-can-practically-smell-it-in-the-air/) poznatog upravitelja fondova s Wall Streeta, Josha Browna:

> "Kupio sam bitcoine kada su koštali $2300, i to mi se udvostručilo gotovo odmah. Onda sam počeo govoriti kako “ne mogu kupiti još” dok im je cijena rasla, premda sam znao da je to razmišljanje bazirano samo na cijenu po kojoj sam ih kupio. Kasnije, kada je cijena pala zbog kineske regulacije mjenjačnica, počeo sam si govoriti, “Odlično, nadam se da će još pasti da mogu kupiti još.”"

Istina leži u tome da su ideje “jeftinog” i “skupog” zapravo besmislene kada govorimo o monetarnim dobrima. Cijena monetarnog dobra ne reflektira njegovu stopu rasprostanjenosti ili korisnosti, nego mjeru koliko je ono široko prihvaćeno da ispuni razne uloge novca.

Dodatna komplikacija u ovom aspektu novca je činjenica da tržišni akteri ne djeluju samo kao nepristrani promatrači koji pokušavaju kupiti i prodati u iščekivanju budućih kretanja monetarne premije, nego i kao aktivni proponenti. Pošto ne postoji objektivno “točna” monetarna premija, širiti dobar glas o superiornijim svojstvima nekog monetarnog dobra je efektivnije nego za obična dobra, čija vrijednost je u konačnici vezana na njegovu osnovnu korisnost. Religiozni zanos sudionika na Bitcoin tržištu vidljiv je na raznim internetskim forumima, gdje Bitcoineri aktivno promoviraju benefine Bitcoina i bogatstvo koje je moguće ostvariti investiranjem u njega. Promatrajući Bitcoin tržište, [Leigh Drogen komentira](https://www.cnbc.com/2017/10/19/josh-brown-goes-down-the-bitcoin-rabbit-hole-commentary.html):

> "To je prepoznatljivo svima kao religija - priča koju si pričamo i oko koje se slažemo. Religija je krivulja na grafu prihvaćanja o kojoj trebamo razmišljati. Sustav je gotovo savršen - onog trenutka kada netko pristupi krugu Bitcoinera, to će reći svima i nastaviti širiti riječ. Onda njihovi prijatelji pristupe i nastave širiti riječ."

Premda usporedba sa religijom može staviti Bitcoin u iracionalno svjetlo, potpuno je racionalno za individualnog vlasnika da širi dobru vijest o superiornom monetarnom dobru, i za šire društvo da se standardizira oko njega. Novac djeluje kao temelj za svu trgovinu i štednju; tako da prihvaćanje superiornog oblika novca ima ogromne multiplicirajuće benefite za stvaranje bogatstva za sve članove društva.

#### Oblik monetizacije

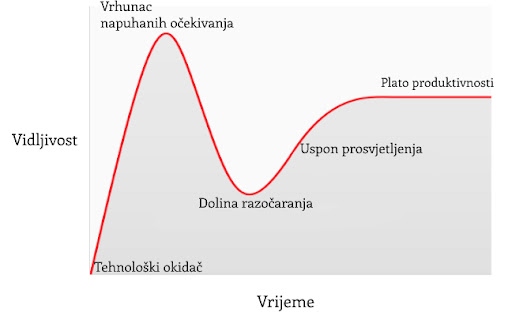

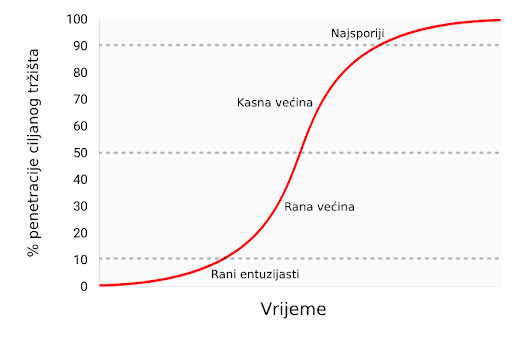

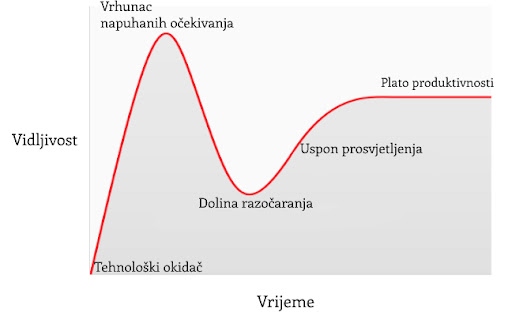

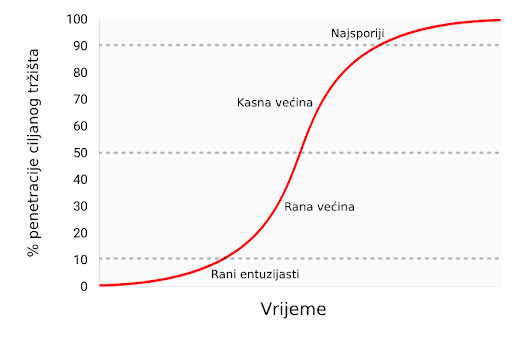

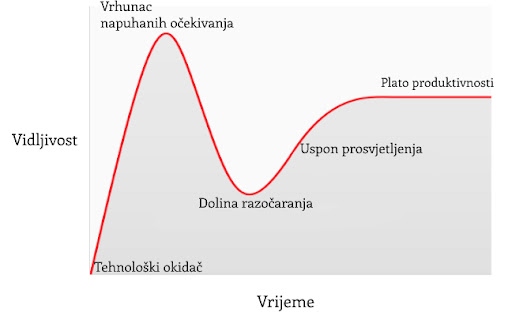

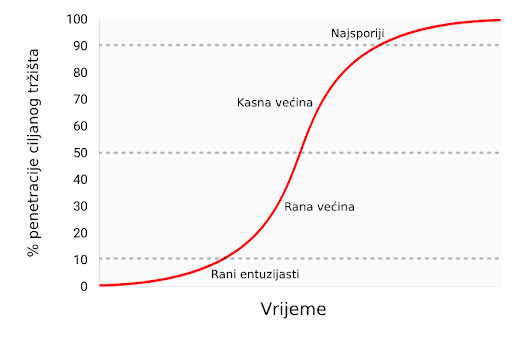

U članku o [Spekulativnom prihvaćanju Bitcoina / teorije cijene](https://medium.com/@mcasey0827/speculative-bitcoin-adoption-price-theory-2eed48ecf7da), Michael Casey postulira da rastući Gartner hype ciklusi predstavljaju faze standardne S-krivulje prihvaćanja novih tehnologija, koje su bile prisutne kod mnogih transformacijskih tehnologija dok su postajale uobičajene u društvu.

Svaki Gartner hype ciklus počinje sa eksplozijom entuzijazma za novom tehnologijom, a cijenu podižu oni sudionici na tržištvu koji su “dostupni” u toj fazi. Najraniji kupci u Gartner hype ciklusu obično imaju jaku vjeru o transformacijskoj prirodi tehnologije u koju ulažu. S vremenom, tržište dosegne vrhunac entuzijazma kako se količina novih kupaca iscrpljuje, te kupovinom počnu dominirati spekulatori koji su više zainteresirani u brze profite nego u samu tehnologiju.

Nakon vrha hype ciklusa, cijene rapidno padaju dok spekulativno ludilo ustupa mjesto očajavanju, javnoj poruzi i osjećaju da tehnologija nije uopće bila transformacijska. S vremenom, cijena dosegne dno i formira plato na kojem se originalnim ulagačima, koji su imali snažno uvjerenje, pridružuju nove grupe ljudi koji su izdržali bol kraha cijena i koji cijene važnost same tehnologije.

Plato traje neko vrijeme i formira, kako Casey kaže, “stabilnu, dosadnu dolinu.” Za ovo vrijeme, javni interes za tehnologiju opada, no nastaviti će se razvijati i snažna zajednica uvjerenja će polako rasti. Tada, postavlja se nova baza za sljedeću iteraciju hype ciklusa, dok vanjski promatrači prepoznaju da tehnologija i dalje postoji i da ulaganje u nju možda nije onoliko rizično kao što se činilo za vrijeme pada cijene. Sljedeća iteracija hype ciklusa donosi mnogo veći broj novih ljudi, pa je i ciklus daleko veći u svojoj magnitudi.

Jako mali broj ljudi koji sudjeluju u Gartner hype ciklusu će točno predvidjeti koliko će visoko cijena porasti za vrijeme ciklusa. Cijene često dosegnu razine koje bi se činile apsurdnima većini ulagača u raniji stadijima ciklusa. Kada ciklus završi, mediji tipično atribuiraju pad cijene nekoj od aktualnih drušvenih tema. Premda takva tema može biti okidač pada, ona nikad nije temeljni razlog zašto ciklus završava. Gartner hype ciklusi završavaju kada je količina dostupnih novih sudionika na tržištu iscrpljena.

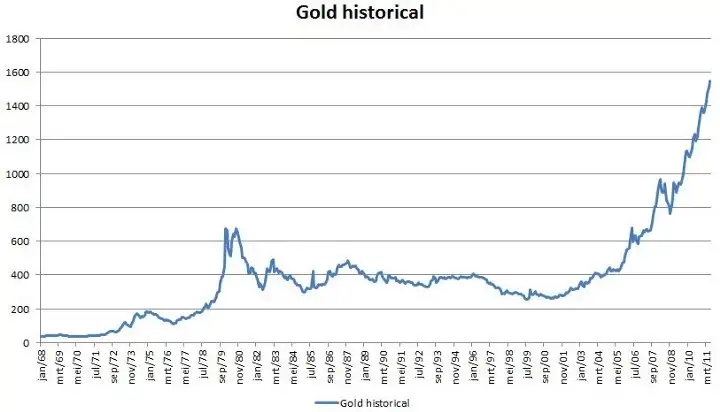

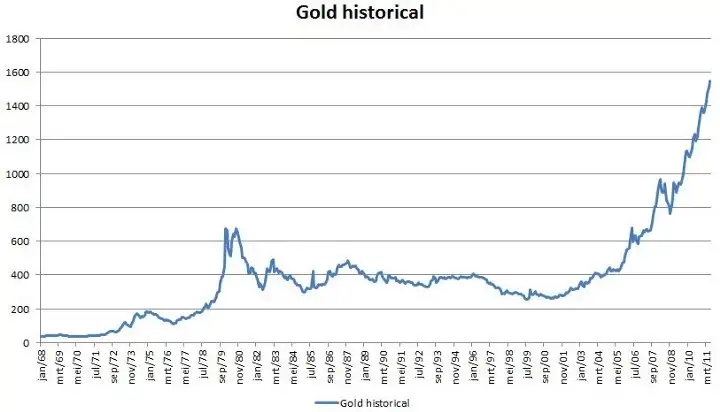

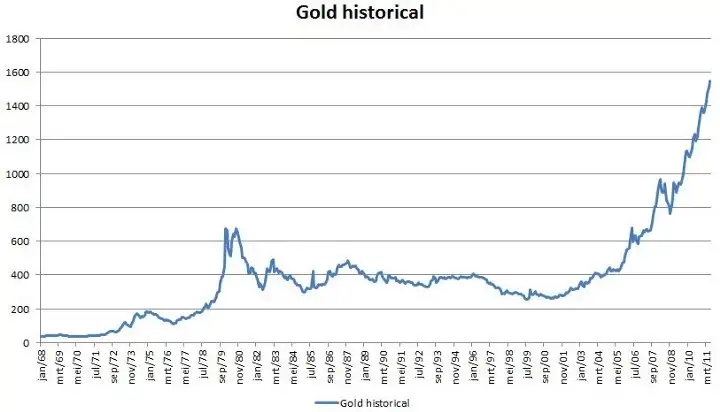

Zanimljivo je da je i zlato nacrtalo klasičan graf Gartner hype ciklusa od kasnih 1970-ih do ranih 2000-ih. Moguće je spekulirati da je hype ciklus osnovna socijalna dinamika oko procesa monetizacije.

#### Gartner kohorte

Od početka trgovanja Bitcoina na mjenjačnicama 2010. godine, Bitcoin tržište je svjedočilo četirima velikim Gartner hype ciklusima. U retrospektivi, možemo vrlo precizno identificirati grupe cijena prethodnih hype ciklusa Bitcoin tržišta. Također, možemo kvalitativno odrediti kohorte ulagača koje su povezane sa svakom iteracijom prethodnih ciklusa.

**$0–$1** (2009. – 3. mjesec 2011.): Prvi hype ciklus u Bitcoin tržištu dominirali su kriptografi, računalni znanstvenici i cypherpunkovi koji su od početka bili spremni razumijeti važnost nevjerojatnog izuma Satoshija Nakamotoa, i koji su bili pioniri u potvrđivanju da Bitcoin protokol nema tehničkih mana.

**$1–$30** (3. mjesec 2011. – 7. mjesec. 2011.): Drugi ciklus privukao je rane entuzijaste oko novih tehnologija kao i stabilan pritok ideološki motiviranih ulagača koji su bili oduševljeni idejom novca odvojenog od države. Libertarijanci poput Rogera Vera došli su u Bitcoin zbog aktivnog anti-institucionalnog stava, i mogućnosti koju je nova tehnologija obećavala. Wences Casares, briljantni i dobro povezani serijski poduzetnik, bio je također dio drugog Bitcoin hype ciklusa te je širio riječ o Bitcoinu među najprominentnijim tehnolozima i ulagačima u Silicijskoj Dolini.

**$250–$1100** (4. mjesec 2013. – 12. mjesec 2013.): Treći hype ciklus doživio je ulazak ranih generalnih i institucionalnih ulagača koji su bili voljni uložiti trud i riskirati kroz užasno komplicirane kanale likvidnosti kako bi kupili bitcoine. Primaran izvor likvidnosti na tržištu za vrijeme ovog perioda bio je MtGox, mjenjačnica bazirana u Japanu, koju je vodio notorno nesposobni i beskrupulozni Mark Karpeles, koji je kasnije završio i u zatvoru zbog svoje uloge u kolapsu MtGoxa.

Valja primijetiti da je rast Bitcoinove cijene za vrijeme spomenuti hype ciklusa većinom povezano sa povećanjem likvidnosti i lakoćom sa kojom su ulagači mogli kupiti bitcoine. Za vrijeme prvog hype ciklusa, nisu postojale mjenjačnice; akvizicija bitcoina se odvijala primarno kroz rudarenje (mining) ili kroz izravnu razmjenu sa onima koju su već izrudarili bitcoine. Za vrijeme drugog hype ciklusa, pojavile su se rudimentarne mjenjačnice, no nabavljanje i osiguravanje bitcoina na ovim mjenjačnicama bilo je previše kompleksno za sve osim tehnološki najsposobnijih ulagača. Čak i za vrijeme trećeg hype ciklusa, ulagači koju su slali novac na MtGox kako bi kupili bitcoine su morali raditi kroz značajne prepreke. Banke nisu bile voljne imati posla sa mjenjačnicom, a oni posrednici koji su nudili usluge transfera bili su često nesposobni, kriminalni, ili oboje. Nadalje, mnogi koji su uspjeli poslati novac MtGoxu, u konačnici su morali prihvatiti gubitak svojih sredstava kada je mjenjačnica hakirana i kasnije zatvorena.

Tek nakon kolapsa MtGox mjenjačnice i dvogodišnje pauze u tržišnoj cijeni Bitcoina, razvili su se zreli i duboki izvori likvidnosti; primjeri poput reguliranih mjenjačnica kao što su GDAX i OTC brokeri kao Cumberland mining. Dok je četvrti hype ciklus započeo 2016. godine, bilo je relativno lako običnim ulagačima kupiti i osigurati bitcoine.

###### $1100–$19600? (2014. –?):

U trenutku pisanja ovog teksta, tržište Bitcoina je prolazilo svoj četvrti veliki hype ciklus. Sudjelovanje u ovom hype ciklusu dominirala je ona skupina koju je Michael Casey opisao kao “rana većina” običnih i institucionalnih ulagača.

Kako su se izvori likvidnosti produbljivali i sazrijevali, veliki institucionalni ulagači sada imaju priliku sudjelovati kroz regulirana “futures” tržišta. Dostupnosti takvih tržišta stvara put ka kreaciji Bitcoin ETF-a (exchange traded fund) (fond na slobodnom tržištu), koji će onda pokrenuti “kasnu većinu” i “najsporije” u sljedećim hype ciklusima.

Premda je nemoguće predvidjeti točan efekt budućih hype ciklusa, razumno je očekivati da će najviša točka biti između $20,000 i $50,000 (2021. zenit je bio preko $69,000). Znatno više od ovog raspona, i Bitcoin bi imao znatan postotak ukupne vijednosti zlata (zlato i Bitcoin bi imali jednaku tržišnu kapitalizaciju kada bi bitcoini vrijedili oko $380,000 u trenutku pisanja ovog teksta). Značajan postotak vrijednosti zlata dolazi od potražnje centralnih banaka, te je malo vjerojatno da će centralne banke ili suverene države sudjelovati u trenutnom hype ciklusu.

#### Ulazak suverenih država u Bitcoin

Bitcoinov zadnji Gartner hype ciklus će započeti kada ga suverene države počnu akumulirati kao dio svojih rezervi stranih valuta. Tržišna kapitalizacija Bitcoina je trenutno premala da bismo ga smatrali značajnim dodatkom rezervama većini zemalja. No, kako se interes u privatnom sektoru povećava i kapitalizacija Bitcoina se približi trilijunu dolara, postat će dovoljno likvidan za većinu država. Prva država koja službeno doda bitcoine u svoje rezerve će vjerojatno potaknuti stampedo ostalih da učine isto. Države koje su među prvima u usvajanju Bitcoina imat će najviše benefita u svojim knjigama ako Bitcoin u konačnici postane globalna valuta (global reserve currency). Nažalost, vjerojatno će države sa najjačom izvršnom vlasti - diktature poput Sjeverne Koreje - biti najbrže u akumulaciji bitcoina. Neodobravanje prema takvim državama i slaba izvršna tijela zapadnjačkih demokracija uzrokovat će sporost i kašnjenje u akumulaciji bitcoina za njihove vlastite rezerve.

Velika je ironija u tome što je SAD trenutno jedna od regulatorno najotvorenijih nacija prema Bitcoinu, dok su Kina i Rusija najzatvorenije. SAD riskira najviše, geopolitički, ako bi Bitcoin zamijenio dolar kao svjetska rezervna valuta. U 1960-ima, Charles de Gaulle je kritizirao “pretjeranu privilegiju” (“exorbitant privilege”) koju su SAD imale u međunarodnom monetarnom poretku, postavljenom kroz Bretton Woods dogovor 1944. godine. Ruska i kineska vlada još ne shvaćaju geo-strateške benefite Bitcoina kao rezervne valute, te se trenutno brinu o efektima koje bi mogao imati na njihova unutarnja tržišta. Kao de Gaulle u 1960-ima, koji je prijetio SAD-u povratkom na klasični standard zlata, Kinezi i Rusi će s vremenom uvidjeti korist u velikoj poziciji u Bitcoinu - spremištu vrijednosti bez pokrića ijedne vlade. Sa najvećom koncentracijom rudara Bitcoina u Kini (2017.), kineska vlada već ima znatnu potencijalnu prednost u stavljanju bitcoina u svoje rezerve.

SAD se ponosi svojim statusom nacije inovatora, sa Silicijskom dolinom kao krunom svoje ekonomije. Dosad, Silicijska dolina je dominirala konverzacijom usmjerenom prema regulaciji, i poziciji koju bi ona treba zauzeti prema Bitcoinu. No, bankovna industrija i federalna rezerva SAD-a (US Federal Reserve, Fed) napokon počinju uviđati egzistencijalnu prijetnju koju Bitcoin predstavlja za američku monetarnu politiku, postankom globalne rezervne valute. Wall Street Journal, jedan od medijskih glasova federalne reserve, izdao je [komentar ](https://www.wsj.com/articles/is-it-time-to-regulate-bitcoin-1512409004) o Bitcoinu kao prijetnji monetarnoj politici SAD-a:

> "Postoji još jedna opasnost, možda i ozbiljnija iz perspektive centralnih banaka i regulatora: bitcoin možda ne propadne. Ako je spekulativni žar u kriptovalutu samo prvi pokazatelj njezinog šireg korištenja kao alternative dolaru, Bitcoin će svakako ugroziti monopol centralnih banaka nad novcem."

U narednim godinama, možemo očekivati veliku borbu između poduzetnika i inovatora u Silicijskoj dolini, koji će pokušavati čuvati Bitcoin od državne kontrole s jedne strane, i bankovne industrije i centralnih banaka koje će učiniti sve što mogu da bi regulirale Bitcoin kako bi spriječile znatne promjene u svojoj industriji i moći izdavanja novca, s druge.

#### Prijelaz na medij razmjene

Monetarno dobro ne može postati opće prihvaćen medij razmjene (standardna ekonomska definicija za “novac”) prije nego je vrednovano od širokog spektra ljudi; jednostavno, dobro koje nije vrednovano neće biti prihvaćeno u razmjeni. Kroz proces generalnog rasta vrijednosti, i time postanka spremišta vrijednosti, monetarno dobro će brzo narasti u kupovnoj moći, i time stvoriti cijenu za korištenje u razmjeni. Samo kada ta cijena rizika mijenjanja spremišta vrijednosti padne dovoljno nisko, može dobro postati opće prihvaćen medij razmjene.

Preciznije, monetarno dobro će biti prikladno kao medij razmjene samo kada je suma cijene rizika i transakcijske cijene u razmjeni manja nego u trgovini bez tog dobra.

U društvu koje vrši robnu razmjenu, prijelaz spremišta vrijednosti u medij razmjene može se dogoditi čak i onda kada monetarno dobro raste u kupovnoj moći, zato što su transakcijski troškovi robne razmjene iznimno visoki. U razvijenoj ekonomiji, u kojoj su troškovi razmjene niski, moguće je za mladu i rapidno rastućnu tehnologiju spremišta vrijednosti, poput Bitcoina, da se koristi kao medij razmjene, doduše na ograničen način. Jedan primjer je ilegalno tržište droge, gdje su kupci voljni žrtvovati oportunu cijenu čuvanja bitcoina kako bi umanjili znatan rizik kupovine droge koristeći fiat novac.

Postoje međutim velike institucionalne barijere da novonastalo spremište vrijednosti postane sveopće prihvaćen medij razmjene u razvijenom društvu. Države koriste oporezivanje kao moćnu metodu zaštite svojeg suverenog novca protiv rivalskih monetarnih dobara. Ne samo da suvereni novac ima prednost konstantnog izvora potražnje, zato što je porez moguće platiti jedino u njemu, nego su i rivalska monetarna dobra oporezana pri svakoj razmjeni za vrijeme rastuće cijene. Ova metoda oporezivanja stvara znatan otpor korištenju spremišta vrijednosti kao medija razmjene.

Ovakvo sabotiranje tržišnih monetarnih dobara nije nepremostiva barijera za njihovo prihvaćanje kao općeg medija razmjene. Ako ljudi izgube vjeru u suvereni novac, njegova vrijednost može rapidno propasti kroz proces zvan hiperinflacija. Kada suvereni novac prolazi kroz hiperinflaciju, njegova vrijednost propadne prvo u usporedbi sa najlikvidnijim dobrima u društvu, kao što je zlato ili stabilna strana valuta (američki dolar npr.), ako su ona dostupna. Kada nema likvidnih dobara ili ih ima premalo, novac u hiperinflaciji kolabira u usporedbi sa stvarnim dobrima, kao što su nekretnine ili upotrebljiva roba. Arhetipska slika hiperinflacije je trgovina sa praznim policama - potrošači brzo bježe iz propadajuće vrijednosti novca svoje nacije.

Nakon dovoljno vremena, kada je vjera potpuno uništena za vrijeme hiperinflacije, suvereni novac više nitko ne prihvaća, te se društvo može vratiti na robnu razmjenu, ili će doživjeti potpunu zamjenu monetarne jedinice za sredstvo razmjene. Primjer ovog procesa bila je zamjena zimbabveanskog dolara za američki dolar. Takva promjena suverenog novca za stranu valutu je dodatno otežana relativnom oskudnošću strane valute i odsustvom stranih bankarskih institucija koje pružaju likvidnost tržištu.

Sposobnost lakog prenošenja bitcoina preko granica i odsustvo potrebe za bankarskim sustavom čine Bitcoin idealnim monetarnim dobrom za one ljude koji pate pod hiperinflacijom. U nadolazećim godinama, kako fiat valute nastave svoj povijesni trend ka bezvrijednosti, Bitcoin će postati sve popularniji izbor za ušteđevine ljudi diljem svijeta. Kada je novac nacije napušten i zamijenjen Bitcoinom, Bitcoin će napraviti tranziciju iz spremišta vrijednosti u tom društvu u opće prihvaćeno sredstvo razmjene. Daniel Krawicz stvorio je termin “[hiperbitcoinizacija](http://nakamotoinstitute.org/mempool/hyperbitcoinization/#selection-43.159-46.0)” da bi opisao ovaj proces.

#### Učestala pogrešna shvaćanja

Većina ovog članka usredotočila se na monetarnu prirodu Bitcoina. Sa tim temeljima možemo adresirati neke od najčešćih nerazumijevanja u Bitcoinu.

##### Bitcoin je balon (bubble)

Bitcoin, kao sva tržišna monetarna dobra, posjeduje monetarnu premiju. Ona često rezultira uobičajenom kritikom da je Bitcoin samo “balon.” No, sva monetarna dobra imaju monetarnu premiju. Naprotiv, ta monetarna premija (cijena viša od one koju diktira potražnja za dobrom kao korisnim) je upravo karakteristična za sve oblike novca. Drugim riječima, novac je uvijek i svuda balon. Paradoksalno, monetarno dobro je istovremeno balon i ispod vrijednosti ukoliko je u ranijim stadijima općeg prihvaćanja kao novac.

##### Bitcoin je previše volatilan

Volatilnost cijene Bitcoina je funkcija njegovog nedavnog nastanka. U prvih nekoliko godina svojeg postojanja, Bitcoin se ponašao kao mala dionica, i svaki veliki kupac - kao npr. braća Winklevoss - mogao je uzrokovati veliki skok u njegovoj cijeni. No, kako su se prihvaćenost i likvidnost povećavali kroz godine, volatilnost Bitcoina je srazmjerno smanjila. Kada Bitcoin postigne tržišnu kapitalizaciju (vrijednost) zlata, imat će sličnu volatilnost kao i zlato. Kako Bitcoin nastavi rasti, njegova volatilnost će se smanjiti do razine koja ga čini prikladnim za široko korištenje kao medij razmjene. Kao što je prethodno rečeno, monetizacija Bitcoina se odvija u seriji Gartner hype ciklusa. Volatilnost je najniža za vrijeme vrhunaca i dolina unutar ciklusa. Svaki hype ciklus ima nižu volatilnost od prethodnih, zato što je likvidnost tržišta veća.

##### Cijene transakcija su previsoke

Novija kritika Bitcoin mreže je ta da ju je povećanje cijena prijenosa bitcoina učinilo neprikladnom za sustav plaćanja. No, rast u cijenama transakcija je zdrav i očekivan. One su nužne za plaćanje bitcoin minera (rudara), koji osiguravaju mrežu validacijom transakcija. Rudare se plaća kroz cijene transakcija ili kroz blok-nagrade, koje su inflacijska subvencija od trane trenutnih vlasnika bitcoina.

S obzirom na Bitcoinovu fiksnu proizvodnju (monetarna politika koja ga čini idealnim za spremanje vrijednosti), blok-nagrade će s vremenom nestati i mrežu će se u konačnici morati osiguravati kroz cijene transakcija. Mreža sa “niskim” cijenama transakcija je mreža sa slabom sigurnosti i osjetljiva na vanjsku intervenciju i cenzuru. Oni koji hvale niske cijene Bitcoinovih alternative zapravo niti ne znajući opisuju slabosti tih takozvanih “alt-coina.”

Površan temelj kritika Bitcoinovih “visokih” cijena transakcija je uvjerenje da bi Bitcoin trebao biti prvo sustav plaćanja, i drugo spremište vrijednosti. Kao što smo vidjeli kroz povijest novca, ovo uvjerenje je naopako. Samo onda kada Bitcoin postane duboko ukorijenjeno spremište novca može biti prikladan kao sredstvo razmjene. Nadalje, kada oportunitetni trošak razmjene bitcoina dođe na razinu koja ga čini prikladnim sredstvom razmjene, većina trgovine neće se odvijati na samoj Bitcoin mreži, nego na mrežama “drugog sloja” (second layer) koje će imati niže cijene transakcija. Takve mreže, poput Lightning mreže, služe kao moderna verzija zadužnica koje su korištene za prijenos vlasničkih papira zlata u 19. stoljeću. Banke su koristile zadužnice zato što je prijenos samog metala bio daleko skuplji. Za razliku od takvih zadužnica, Lightning mreža će omogućavati nisku cijenu prijenosa bitcoina bez potrebe za povjerenjem prema trećoj strani, poput banaka. Razvoj Lightning mreže je tehnološka inovacija od izuzetne važnosti u povijesti Bitcoina, i njezina vrijednost će postati očita u narednim godinama, kako je sve više ljudi bude razvijalo i koristilo.

##### Konkurencija

Pošto je Bitcoin softverski protokol otvorenog tipa (open-source), oduvijek je bilo moguće kopirati softver i imitirati mrežu. Kroz godine nastajali su mnogi imitatori, od identičnih kopija, kao Litecoin, do kompleksnijih varijanti kao što je Ethereum, koje obećavaju arbitrarno kompleksne ugovorne mehanizme koristeći decentralizirani računalni sustav. Česta kritika Bitcoinu od strane ulagača je ta da on ne može zadržati svoju vrijednost kada je vrlo lako stvoriti konkurente koji mogu lako i brzo u sebi imati najnovije inovacije i softverske funkcionalnosti.

Greška u ovom argumentu leži u manju takozvanog “mrežnog efekta” (network effect), koji postoji u prvoj i dominantnoj tehnologiji u nekom području. Mrežni efekt - velika vrijednost korištenja Bitcoina samo zato što je već dominantan - je važno svojstvo samo po sebi. Za svaku tehnologiju koja posjeduje mrežni efekt, to je daleko najvažnije svojstvo koje može imati.

Za Bitcoin, mrežni efekt uključuje likvidnost njegovog tržišta, broj ljudi koji ga posjeduju, i zajednicu programera koji održavaju i unaprjeđuju njegov softver i svjesnost u javnosti. Veliki ulagači, uključujući države, će uvijek prvo tražiti najlikvidnije tržište, kako bi mogli ući i izaći iz tržišta brzo, i bez utjecanja na cijenu. Programeri će se pridružiti dominantnoj programerskoj zajednici sa najboljim talentom, i time pojačati samu zajednicu. Svjesnost o brendu sama sebe pojačava, pošto se nadobudni konkurenti Bitcoina uvijek spominju u kontekstu Bitcoina kao takvog.

##### Raskrižje na putu (fork)

Trend koji je postao popularan 2017. godine nije bio samo imitacija Bitcoinovog softvera, nego kopiranje potpune povijesti njegovih prošlih transakcija (cijeli blockchain). Kopiranjem Bitcoinovog blockchaina do određene točke/bloka i odvajanjem sljedećih blokova ka novoj mreži, u procesu znanom kao “forking” (odvajanje), Bitcoinovi konkurenti su uspjeli riješiti problem distribuiranja svojeg tokena velikom broju korisnika.

Najznačajniji takav fork dogodio se 1. 8. 2017. godine, kada je nova mreža nazvana Bitcoin Cash (Bcash) stvorena. Vlasnik N količine bitcoina prije 1.8.2017. bi onda posjedovao N bitcoina i N BCash tokena. Mala, ali vrlo glasna zajednica Bcash proponenata je neumorno pokušavala prisvojiti Bitcoinov brend i ime, imenujući svoju novu mrežu Bitcoin Cast i pokušavajući uvjeriti nove pridošlice u Bitcoin da je Bcash “pravi” Bitcoin. Ti pokušaji su većinom propali, i taj neuspjeh se vidi u tržišnim kapitalizacijama dviju mreža. No, za nove ulagače, i dalje postoji rizik da bi konkurent mogao kopirati Bitcoin i njegov blockchain i tako uspjeti u preuzimanju tržišne kapitalizacije, te postati de facto Bitcoin.

Moguće je uočiti važno pravilo gledajući velike forkove u prošlosti Bitcoin i Ethereum mreža. Većina tržišne kapitalizacije odvijat će se na mreži koja zadrži najviši stupanj talenta i aktivnosti u zajednici programera. Premda se na Bitcoin može gledati kao na nov i mlad novac, on je također računalna mreža koja počiva na softveru, kojeg se pak treba održavati i poboljšavati. Kupovina tokena na mreži koja ima malo neiskusnih programera bilo bi kao kupovati kopiju Microsoft Windowsa na kojoj rade lošiji programeri. Jasno je vidljivo iz povijesti forkova koji su se odvili 2017. godine da su najbolji računalni i kriptografski stručnjaci posvećeni razvoju originalnog Bitcoina, a ne nekoj od rastućeg broja imitacija koje su se izrodile iz njega.

#### Stvarni rizici

Premda su uobičajene kritike upućene Bitconu od strane medija i ekonomske profesije krive i bazirane na netočnom shvaćanju novca, postoje pravi i značajni rizici kod ulaganja u Bitcoin. Bilo bi mudro za novog Bitcoin ulagača da shvati ove rizike prije potencijalnog ulaganja.

##### Rizik protokola

Bitcoin protokol i kriptografski sastavni dijelovi na kojima je sagrađen potencijalno imaju dosad nepronađenu grešku u svom dizajnu, ili mogu postati nesigurni razvojem kvantnih računala. Ako se pronađe greška u protokolu, ili neka nova metoda računarstva učini mogućim probijanje kriptografskih temelja Bitcoina, vjera u Bitcoin biti će znatno narušena. Rizik protokola bio je najviši u ranim godinama razvoja Bitcoina, kada je još uvijek bilo nejasno, čak i iskusnim kriptografima, je li Satoshi Nakamoto zaista riješio problem bizantskih generala (Byzantine Generals’ Problem). Brige oko ozbiljnih grešaka u Bitcoin protokolu nestale su kroz godine, no uzevši u obzir njegovu tehnološku prirodu, rizik protokola će uvijek ostati u Bitcoinu, makar i kao izuzetak.

##### Propadanje mjenjačnica

Time što je decentraliziran, Bitcoin je pokazao značajnu otpornost, suočen sa brojnim pokušajima raznih vlada da ga reguliraju ili unište. No, mjenjačnice koje trguju bitcoinima za fiat valute su centralizirani entiteti i podložne regulacijama i zatvaranju. Bez mjenjačnica i volje bankara da s njima posluju, proces monetizacije Bitcoina bio bi ozbiljno usporen, ako ne i potpuno zaustavljen. Iako postoje alternativni izvori likvidnosti za Bitcoin, poput “over-the-counter” brokera i decentraliziranih tržišta za kupovinu i prodaju bitcoina, kritičan proces otkrivanja i definiranja cijene se odvija na najlikvidnijim mjenjačnicama, koje su sve centralizirane.

Jedan od načina za umanjivanje rizika gašenja mjenjačnica je geografska arbitraža. Binance, jedna od velikih mjenjačnica iz Kine, preselila se u Japan nakon što joj je kineska vlada zabranila operiranje u Kini. Vlade su također oprezne kako ne bi ugušile novu industriju koja je potencijalno značajna kao i internet, i time predale nevjerojatnu konkurentnu vrijednost drugim nacijama.

Samo kroz koordinirano globalno ukidanje Bitcoin mjenjačnica bi proces monetizacije mogao biti zaustavljen. Trenutno smo u utrci; Bitcoin raste i postaje sve rašireniji, i doći će do trenutka kada bi potpuno ukidanje mjenjačnica postalo politički neizvedivo - kao i gašenje interneta. Mogućnost takvog ukidanja je još uvijek realna, i valja je uzeti u obzir pri ulaganju u Bitcoin. Kao što je gore objašnjeno, suverene vlade se polako bude i uviđaju prijetnju koju predstavlja neovisna digitalna valuta otporna na cenzuru, za njihovu monetarnu politiku. Otvoreno je pitanje hoće li išta poduzeti da odgovore ovoj prijetnji prije nego Bitcoin postane toliko utvrđen i raširen da politička akcija postane nemoćna i ne-efektivna.

##### Zamjenjivost

Otvorena i transparentna priroda Bitcoin blockchaina omogućava državama da proglase specifične bitcoine “okaljanima” zbog njihovog korištenja u određenim aktivnostima. Premda Bitcoin, na protokolarnoj razini, ne diskriminira transakcije na ikoji način, “okaljani” bitcoini bi mogli postati bezvrijedni ako bi ih regulacije proglasile ilegalnima i neprihvatljivima za mjenjačnice ili trgovce. Bitcoin bi tada izgubio jedno od kritičnih svojstava monetarnog dobra: zamjenjivost.

Da bi se ovaj problem riješio i umanjio, biti će potrebna poboljšanja na razini protokola kako bi se poboljšala privatnost transakcija. Premda postoji napredak u ovom smjeru, prvi put primjenjen u digitalnim valutama kao što su Monero i Zcash, potrebno je napraviti značajne tehnološke kompromise između efikasnosti i kompleksnosti Bitcoina i njegove privatnosti. Pitanje ostaje otvoreno je li moguće dodati nova svojstva privatnosti na Bitcoin, na način koji neće kompromitirati njegovu korisnost kao novca.

#### Zaključak

Bitcoin je novonastali novac koji je u procesu transformacije iz sakupljačkog dobra u spremište vrijednosti. Kao neovisno monetarno dobro, moguće je da će u budućnosti postati globalan novac, slično kao zlato za vrijeme 19. stoljeća. Prihvaćanje Bitcoina kao globalnog novca je upravo taj optimističan scenarij za Bitcoin, kojeg je artikulirao Satoshi Nakamoto još 2010. godine u [email razmjeni](https://pastebin.com/Na5FwkQ4) sa Mikeom Hearnom:

> "Ako zamisliš da se koristi u nekom dijelu svjetske trgovine, i da će postojati samo 21 milijun bitcoina za cijeli svijet, vrijednost po jedinici će biti znatno veća".

Ovaj scenarij je još snažnije definirao briljantni kriptograf Hal Finney, koji je ujedno primio i prve bitcoine od Nakamotoa, ubrzo nakon [najave prvog funkcionalnog Bitcoin softvera](https://www.mail-archive.com/cryptography@metzdowd.com/msg10152.html):

> "Zamislimo da Bitcoin bude uspješan i postane dominantan sustav plaćanja diljem svijeta. U tom slučaju će ukupna vrijednost valute biti jednaka ukupnoj vrijednosti svog bogatstva svijeta. Današnje procjene ukupnog svjetskog bogatska kućanstava koje sam pronašao borave negdje između 100 i 300 trilijuna dolara. Sa 20 milijuna bitcoina, svaki bi onda vrijedio oko 10 milijuna dolara."

Čak i da Bitcoin ne postane u cijelost globalan novac, nego da se samo natječe sa zlatom kao neovisno spremište vrijednosti, i dalje je masivno podcijenjen. Mapiranje tržišne kapitalizacije postojeće količine izrudarenog zlata (oko 8 trilijuna dolara) na maksimalnu dostupnost Bitcoina od 21 milijun, daje vrijednost od otprilike 380,000 dolara po bitcoinu. Kao što smo vidjeli u prethodnom tekstu, svojstva koja omogućavaju monetarnom dobru da bude prikladno spremište vrijednosti, čine Bitcoin superiornijim zlatu u svakom pogledu osim trajanja povijesti. No, kako vrijeme prolazi i Lindy efekt postane jači, dosadašnja povijest će prestati biti prednost zlata. Samim time, nije nerazumno očekivati da će Bitcoin narasti do, a možda i preko, ukupne cijene zlata na tržištvu do 2030. Opaska ovoj tezi je činjenica da veliki postotak vrijednosti zlata dolazi od toga što ga centralne banke čuvaju kao spremište vrijednosti. Da bi Bitcoin došao do te razine, određena količina suverenih država će trebati sudjelovati. Hoće li zapadnjačke demokracije sudjelovati u vlasništvu Bitcoina je nepoznato. Vjerojatnije je, nažalost, da će prve nacije u Bitcoin tržištu biti sitne diktature i kleptokracije.

Ako niti jedna država ne bude sudjelovala u Bitcoin tržištu, optimistična teza i dalje postoji. Kao nevisno spremište vrijednosti u rukama individualnih i institucionalnih ulagača, Bitcoin je i dalje vrlo rano u svojoj “krivulji prihvaćenosti” (adoption curve); tzv. “rana većina” ulaze na tržište sada, dok će ostali ući tek nekoliko godina kasnije. Sa širim sudjelovanjem individualnih i institucionalnih ulagača, cijena po bitcoinu između 100,000 i 200,000 dolara je sasvim moguća.

Posjedovanje bitcoina je jedna od malobrojnih asimetričnih novčanih strategija dostupnih svakome na svijetu. Poput “call” opcija, negativan rizik ulagača je ograničen na 1x, dok potencijalna dobit i dalje iznosi 100x ili više. Bitcoin je prvi istinski globalan balon čija je veličina ograničena samo potražnjom i željom građana svijeta da zaštite svoju ušteđevinu od raznovrsnih ekonomskih malverzacija vlade. Bitcoin je ustao kao feniks iz pepela globalne financijske krize 2008. godine - katastrofe kojoj su prethodile odluke centralnih banaka poput američke Federalne rezerve (Federal Reserve).

Onkraj samo financijske teze za Bitcoin, njegov rast i uspjeh kao neovisno spremište vrijednosti imat će duboke geopolitičke posljedice. Globalna, ne-inflacijska valuta će prisiliti suverene države da promjene svoje primarne mehanizme financiranja od inflacije u izravno oporezivanje; koje je daleko manje politički popularno. Države će se smanjivati proporcionalno političkoj boli koju im nanese oporezivanje kao jedini način financiranja. Nadalje, globalna trgovina vršiti će se na način koji zadovoljava aspiraciju Charlesa de Gaullea, da nijedna nacija ne bi smjela imati privilegiju nad ikojom drugom:

> "Smatramo da je potrebno da se uspostavi međunarodna trgovina, kao što je bio slučaj prije velikih nesreća koje su zadesile svijet, na neosporivoj monetarnoj bazi, koja ne nosi na sebi oznaku ijedne države."

Za 50 godina, ta monetarna baza biti će Bitcoin.

-

@ 2e8970de:63345c7a

2025-01-22 18:11:07

So, I'm surprised there isn't a discussion about the Stargate project here already. It got posted twice: https://stacker.news/items/858961 https://stacker.news/items/859422 but to me the big elephant in the room is ... that 500b is a big f*cking number?

https://xcancel.com/elonmusk/status/1881923570458304780

https://www.wsj.com/tech/musk-pours-cold-water-on-trump-backed-stargate-ai-project-53428d16?mod=WSJ_home_mediumtopper_pos_1

Other things that don't make sense

- Why Oracle? OpenAIs long term partner is Microsoft and there is no reason to think Microsoft would have worse access to chips and scaling energy than Oracle

- Trump backed? And Elon seems to hate it? What gives?

- 100b immediately? From where? OpenAIs private valuation is like 100b or 150b so?

originally posted at https://stacker.news/items/860325

-

@ 554ab6fe:c6cbc27e

2025-01-22 17:57:30

In recent years, mindfulness meditation has been gaining traction as a form of therapy to address various health-related issues. In a previous blog [post](https://highlighter.com/a/naddr1qvzqqqr4gupzq422kmldvavct44endu667mcfluv5jjmqfmcsyhpj68wurrvhsn7qy2hwumn8ghj7un9d3shjtnyv9kh2uewd9hj7qq6gyk5ymrpwd6z6ar0946xsefd2pshxapdxehnzwtk0qdvxqdt), I discussed how meditation is a promising technique to alleviate anxiety and depression. Previously, I examined the effects of mindfulness meditation through a psychological perspective. However, I find that the science of meditation is a hard sell for many people; people who come from a more scientific background often need to understand the underlying physiologic mechanisms of mindfulness meditation to be convinced of its efficacy. This is understandable -- I seek these kinds of answers as well. The science of meditation is still very new, and no one has a clear understanding of why it works. However, my research has led me to discover a few promising theories from a bottom-up point of view. How does the practice of meditation change the body, and do these changes then influence the state of the mind?

Meditation appears beneficial to the body, in part, because it increases parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) activity, and decreases sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activity. The SNS is activated during times of danger, and is often called the “fight or flight” response. This response is healthy in moments of danger but becomes detrimental when it is chronically activated. Modern life is full of stressors that keeps the SNS activated, and this chronic SNS activity is poor for our health. Meditation helps us decrease the activation though eliciting the ancillary PNS. But how? The two theories I will outline below all revolve around the effect slow breathing has on increasing parasympathetic activity through vagal tone. More specifically, these theories outline how breathing patterns affect the activation of baroreceptors within blood vessels, and mechanoreceptors within the lungs (Gerritsen & Band, 2018).

Baroreceptors are pressure sensors found within our body. These are important detectors within blood vessels that help relay sensory information to the brain for autonomic control, which helps maintain balance within the cardiovascular systems. For instance, inhalation causes an increase in heart rate, while exhalation causes the heart rate to slow. This is called respiratory sinus arrhythmia (RSA). The detection and signaling of this change, in part, is sensed by baroreceptors within the veins (Gary G. Berntson, John T. Cacioppo, 1993; Karemaker, 2009). The baroreceptors are activated when blood pressure increases in the aorta during exhalation due to increased intra-thoracic pressure. The activation signals a decrease in heart rate that causes a reduction in blood pressure, and vice versa (Gerritsen & Band, 2018; Lehrer & Gevirtz, 2014; Vaschillo et al., 2002). This is one example of the many methods in which balance is maintained within the cardiovascular system via the vagus nerve. Keep in mind that the sensitivity and responsiveness of these receptors can change, which thereby changes the frequency (or tone) of vagus nerve activation. It has been shown that decreasing one’s breath to 0.1 Hz (about 10 seconds per breath) increases the sensitivity of heart rate change given changes in blood pressure (Bernardi et al., 2001; Lehrer et al., 2003). This suggests that the baroreceptors become more sensitive during deep/slow breathing, and the vagus nerve is activated more often. Thus, breathing at this rate increases the sensitivity of these receptors, thereby increasing vagal tone.

Other research has also confirmed that slow breathing rates result in increased heart rate variability (HRV)(Song & Lehrer, 2003). As the name suggests, heart rate variability represents the variability of time intervals between consecutive heartbeats (Makivić et al., 2013). The heart changes speed given the demand of the body. This flexibility of the heart to change its speed quickly is known as heart rate variability. If the speed at which the heart beats changes is fast, the HRV is said to increase. This observation that slower breathing increases HRV makes sense because it is commonly used as an indicator of autonomic nervous system balance (Ernst, 2017) and is increased with increased vagal tone (Laborde et al., 2017). Consequently, because modern day stress causes us to go into “fight or flight” mode often, increasing SNS activity and decreasing PNS activity, decreased HRV can be used as an indicator of stress (Kim et al., 2018). This is important because this breathing frequency of 0.1Hz is the same breathing rate observed in novice Zen meditators (Cysarz & Büssing, 2005). Since meditation results in calmed breathing, it thereby increases vagal tone, and decreases the physiologic processes of stress.

In more simplistic terms, the pace of slowed and consistent breathing increases baroreceptor sensitivity which increases vagal tone because this nerve is what sends the signals of the receptors to the brain (Lehrer et al., 2003). Vagus nerve tone is a major driver of parasympathetic nervous system activity. Due to the vagus nerve innervating all major systems of the body, when activation is increased in one area, activation is increased in the rest. This counteracts the SNS activity caused by stress, which theoretically should balance the body and improve health.

The above theory describes how breathing patterns influence baroreceptors, which influence vagus nerve tone. Another theory argues that it is the receptors within the lungs that cause the physiologic changes(Noble & Hochman, 2019). Within the lungs, there are two pulmonary stretch receptors worth noting: rapidly-adapting receptors (RARs) and slowly-adapting receptors (SARs). RARs are typically activated throughout normal breathing(Noble & Hochman, 2019), while slower breathing additionally activates SARs(Jerath et al., 2006; Schelegle, 2003). SARs are important receptors as they are involved in the Hering-Breur Reflex(Schelegle, 2003), which is a reflex that induces immediate exhalation of the lungs after the detection of an excessively large inhale(Moore, 1927). This reflex likely exists to protect the lungs from overexpansion, but also highlights the importance of the role of these receptors in the nervous system’s control over the lungs.

SARs send signals to a region of the brain called the nuclear tractus solataris (NTS) via the vagus nerve(Schelegle, 2003). The NTS is a relay station for all vagal afferents(Noble & Hochman, 2019), and sends neuronal input to the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus and the central nucleus of the amygdala(Petrov et al., 1993). The amygdala is highly involved in emotional regulation and processing(Desbordes et al., 2012). Increased amygdala activity is also associated with perceived stress(Taren et al., 2015). SARs activation either directly, or indirectly inhibits amygdala activation by means of the NTS(Noble & Hochman, 2019). This possibly explains how deep breathing can provide stress-reducing effects(Noble & Hochman, 2019).